#83 Building Blocks of Corporate Accounting: Intercorporate Shenanigans

Debt buried, revenue faked—a look at how Pescanova and Wirecard did it.

When you open a company's financial statements, you expect clarity—clean numbers telling you exactly what's happening behind the scenes. But as investors, we quickly learn that clarity is often the exception, not the rule. Sometimes, the financial statements we're relying on don't just obscure reality—they actively distort it.

In my last article, we explored the basics of intercorporate accounting—how companies account for investments in other businesses through methods like the cost method, equity method, and full consolidation. Yet knowing the rules is only half the battle. Because the moment accounting standards meet incentives to deceive, those carefully designed rules quickly become tools of deception. Companies stretch them, twist them, and occasionally outright break them. And when that happens, even seasoned investors get fooled.

Look at Pescanova and Wirecard—two companies from entirely different industries and countries. Pescanova, once Spain’s seafood giant, and Wirecard, Germany’s fintech darling, both appeared rock-solid on paper. Regulators approved, auditors signed off, and institutional investors happily bought in. Then, reality hit—hard. Both companies collapsed spectacularly, dragging investors down with them, revealing massive debts hidden in offshore subsidiaries and billions of revenues that existed only in intercompany fantasies.

Why were Pescanova and Wirecard able to fool so many for so long? The answer lies precisely in the opaque structures and intercorporate complexities that we unpacked previously. This time, we won’t just show you how the accounting works. We'll show how the accounting breaks—and how companies misuse intercorporate rules to hide debts, fake revenues, and inflate profits. Because, as we'll see, the most dangerous risks aren't those hidden in complexity—they’re hidden in plain sight, right there on the balance sheet you trusted.

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

I. Why intercorporate structures invite shenanigans

Financial deception doesn’t happen in a vacuum—it’s born from pressure. CEOs need growth to satisfy markets, CFOs must manage debt ratios, and boards often tie executive bonuses to hitting ever-higher earnings targets. These aren’t abstract goals; they’re powerful incentives. And powerful incentives create powerful temptations—especially when accounting rules offer plenty of loopholes.

Intercorporate accounting, by its nature, provides exactly those loopholes. Companies use affiliates—subsidiaries, associates, joint ventures—to pursue legitimate business opportunities. But when pressure mounts and performance stumbles, management can misuse those same affiliates to quietly hide problems. Debt disappears into unconsolidated entities. Revenue magically appears through transactions with related parties. Margins get inflated by shifting costs into partially owned ventures.

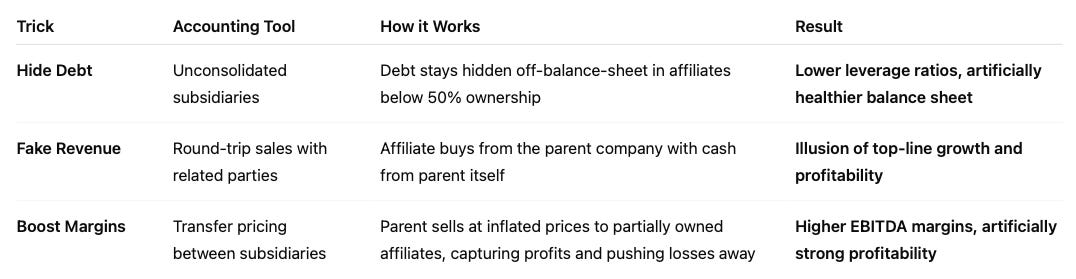

Here’s a simple framework to visualize the main accounting tricks enabled by affiliates:

Hide debt: A company creates or uses affiliates where it owns less than 50% — just enough to avoid "control" under consolidation rules (IFRS 10 or ASC 810). Even if the parent funds the affiliate, or guarantees its loans, as long as it doesn't officially control it, the affiliate’s liabilities don’t show up on the parent company’s balance sheet.

Fake revenue: The company sets up or funds related entities that pose as independent customers. It then sells products or services to these entities, booking it as legitimate revenue. In truth, the cash used by the “customer” may have come from the company itself — via loans, marketing payments, or off-the-books financing.

Boost margins: The parent company sells goods or services to an affiliate or JV it owns, say, 30%. It sells at inflated prices, booking high profits. The affiliate eats the inflated costs, but since only 30% of the affiliate’s loss flows back to the parent (via equity method), the other 70% is “outsourced.” The parent books 100% of the gain on the transaction, but only absorbs a fraction of the cost impact from the affiliate. The result is asymmetric — a sort of profit laundering.

None of these tactics necessarily break accounting rules outright, at least initially. In fact, they often begin by exploiting genuine gray areas—using subtle tricks like careful structuring to keep subsidiaries below consolidation thresholds or cleverly timed transactions that auditors find hard to challenge. Over time, the line between aggressive accounting and outright fraud blurs, often unnoticed by investors until it’s too late.

How did they manage to deceive investors, regulators, and auditors alike? How can you spot similar manipulations before they cause real damage?

Let’s take a closer look.

II: Pescanova – Enron at sea

Pescanova, once considered Spain’s seafood titan, managed a truly impressive feat: they convinced investors, auditors, and bankers for years that everything was just fine, while quietly hiding billions in debt beneath a tangled web of affiliates.

On the surface, Pescanova was a solid business: fishing fleets around the world, processing plants across multiple continents, and an ambitious international expansion. The story resonated well with investors, particularly in the mid-2000s, as Spain's economy boomed. Investors saw steady growth, seemingly controlled debt levels, and consistent profits—exactly what you’d expect from a thriving global player.

But beneath the reassuring headlines and glossy annual reports lay a parallel reality: Pescanova was amassing enormous debts—over €3 billion—that weren’t showing up clearly anywhere on its balance sheet. How was this possible?

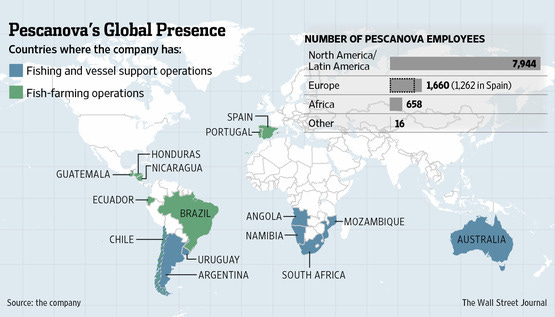

The trick was, unsurprisingly, hidden deep inside Pescanova’s labyrinthine corporate structure. Between subsidiaries, joint ventures, and affiliates, Pescanova had constructed an ecosystem of more than 80 companies around the globe. Many of these were based in offshore jurisdictions or structured so opaquely that even regulators struggled to determine who really controlled them.

How does debt disappears

To understand exactly what Pescanova did, you need to know a bit about consolidation rules (remember those from the last article?). Under IFRS (specifically IFRS 10, previously IAS 27), companies must consolidate subsidiaries that they “control”—typically meaning they hold over 50% of shares or exert significant decision-making influence.

But consolidation isn’t always black-and-white. IFRS rules are principles-based, leaving substantial room for interpretation. Pescanova exploited this flexibility ruthlessly, ensuring that many entities—particularly those carrying significant debt—were carefully structured so they appeared outside the direct control of the parent. In reality, these companies were fully funded by Pescanova, directly or indirectly, through guarantees or hidden agreements.

By creating subsidiaries that technically sat just below the consolidation threshold (often just below 50% ownership), Pescanova legally avoided putting their massive debts onto its consolidated balance sheet. These were debts incurred to finance aggressive expansions—like shrimp farms in Ecuador, fish processing plants in Namibia, and ambitious salmon-farming ventures in Chile. Investors saw ambitious expansion, but not the corresponding liabilities.

Let’s illustrate this with a simplified numerical example:

Suppose Pescanova invests in a shrimp farm in Ecuador.

The project costs €200 million, funded primarily by debt (say €160 million).

Instead of funding it directly (and consolidating the debt), Pescanova sets up a special-purpose subsidiary, "ShrimpCo," and deliberately takes a 49% stake.

Pescanova provides implicit guarantees or secret backstops for ShrimpCo's loans but officially declares no direct control.

ShrimpCo borrows €160 million from banks. Pescanova’s consolidated accounts show no debt, just a simple investment line item labeled “Investment in Associates.”

The real picture looks like this:

Consolidated (What Investors Saw): Investment in Associate: €40M

Reality: Debt at ShrimpCo: €160M hidden from Pescanova’s balance sheet

Multiply this scenario by dozens of similar offshore entities—each with tens or hundreds of millions in hidden debt—and you quickly accumulate billions in invisible obligations.

Fake revenues from non-existent customers

Pescanova’s accounting creativity wasn’t limited to hiding debt. They simultaneously inflated revenues through fictitious or exaggerated intercompany sales. Here’s how it worked:

Pescanova’s parent entity would "sell" products to a shell subsidiary or affiliate at inflated prices.

The affiliate would then record fake sales (often to other controlled entities), recognizing substantial revenue growth.

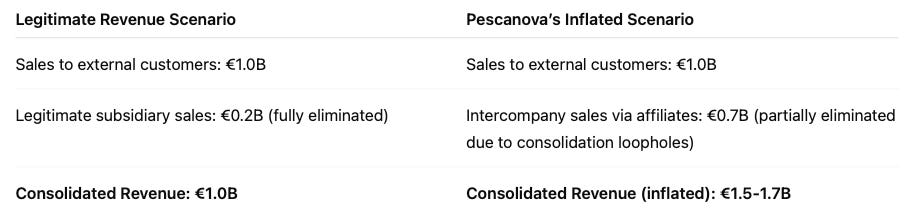

On consolidation, some of these intercompany transactions should eliminate—meaning revenues and profits from internal sales typically disappear when financial statements consolidate. But crucially, if the entities involved weren’t fully consolidated (below 50%), the transactions never canceled out fully.

Pescanova thus created the illusion of steady revenue growth and robust profitability—despite many sales being little more than accounting mirages.

Numerically, the revenue illusion could look like this:

The collapse

This scheme worked astonishingly well—until reality eventually forced its way through. By early 2013, Pescanova faced liquidity constraints as hidden debts came due and revenues failed to translate into real cash. Auditors began demanding answers. Regulators grew suspicious. Bankers became uneasy.

When Pescanova failed to file audited financial statements for 2012, alarms went off. Investigations quickly uncovered the "parallel" accounting system the company had maintained—one for public consumption and another hidden from view, a system CNMV (Spanish regulators) called "filled with junk."

Within months, the full scale of Pescanova’s hidden liabilities emerged: debts totaling over €3.3 billion—more than double what had been publicly reported. The revelation shocked markets, crushed shareholders, and forced the company into bankruptcy. Ultimately, 19 former executives—including Chairman Manuel Fernández de Sousa—faced criminal charges for fraud, money laundering, and falsifying accounts.

Ironically, Pescanova’s auditors, BDO, whose very job was to prevent this kind of deception, had themselves been complicit or grossly negligent. A Spanish court fined BDO €120 million in 2020, convicting a partner who had signed off on the sham accounts.

How investors could have spotted the red flags

Looking back, the red flags were there, hiding in plain sight:

Complexity: Excessive subsidiaries, especially offshore or minority-owned entities, usually mean something more than "business needs" is at play.

Debt vs. Cash Flow: While Pescanova reported solid EBITDA growth, operating cash flows lagged significantly—a telltale sign profits might not be real.

Related-party notes and footnotes: Financial statements always contain obscure footnotes and related-party disclosures. If these are opaque or insufficiently explained, beware.

Insider selling: Executives quietly selling significant stakes, especially without proper notification, should always be treated as suspicious.

Pescanova’s investors missed these signals. They trusted headline figures and seemingly robust financial statements, believing they were backed by economic reality rather than intercorporate tricks.

While accounting standards have tightened since then, the lesson remains clear: Complexity is not always innocent. If something feels overly complicated, opaque, or confusing in a company’s corporate structure, don’t assume it’s your lack of understanding. More often than you’d expect, complexity is deliberately constructed to conceal uncomfortable truths.

III. Wirecard: the great pretender

Pescanova’s seafood fraud might make you think you’ve already seen peak corporate audacity, but don’t worry—Wirecard is here to raise the bar. After all, why settle for simply hiding billions of euros of debt when you can make billions disappear entirely—or better yet, conjure them from thin air? Welcome to Wirecard, Germany’s fintech wunderkind that turned out to be less “fintech” and more “fiction-tech.”

Too good to be true?

Wirecard’s rise was spectacular. Here was a company seemingly at the cutting edge of technology: revolutionizing digital payments, gaining entry to Germany’s DAX 30 index, and achieving growth rates that made even Silicon Valley blush. Auditors gave it the thumbs up, banks competed to lend money, and institutional investors piled in enthusiastically. Wirecard appeared unstoppable—until, of course, it abruptly stopped.

In June 2020, after years of glowing financial reports and promises of unstoppable growth, Wirecard spectacularly imploded. Auditors admitted they couldn’t verify an incredible €1.9 billion in cash, which management casually described as “missing.” Imagine casually losing track of almost €2 billion—Wirecard made it sound like misplacing your keys.

Yet the truth was more absurd: the money never existed. Wirecard’s “missing cash” was merely the culmination of years spent inflating revenues and profits through an elaborate system of fictitious intercompany and third-party transactions.

How did the do it?

Wirecard’s fraud hinged on the oldest trick in the corporate fraud book: creating fake sales. But Wirecard wasn’t content with mere amateur theatrics; their scheme had layers of sophisticated complexity. Here’s how it worked:

Wirecard claimed to operate through an international network of “third-party acquiring partners,” particularly in exotic and conveniently distant markets like Dubai, the Philippines, and Singapore. These partners supposedly processed massive volumes of payments for merchants—payments that generated hundreds of millions in revenues and profits for Wirecard. The partners were critical, accounting for roughly half of Wirecard’s global revenue at their peak.

The only slight problem? Many of these partners weren’t exactly robust, independent businesses. In fact, many weren’t even real. Instead, they were obscure shell companies with vague ownership structures, quietly managed by individuals mysteriously connected to Wirecard itself.

A simplified version of Wirecard’s illusion:

Wirecard HQ (in Germany) announces revenues of, say, €2 billion from payment processing services worldwide.

Third-party partner ("TPP") in the Philippines or Dubai “confirms” processing payments worth billions.

Auditors ask to verify these figures. Wirecard casually responds that TPP manages these revenues and holds the cash in escrow accounts.

Auditors accept superficial proof—often just fabricated documents and spreadsheets, verified by cooperating bank officers (occasionally bribed or simply incompetent).

In reality, no meaningful economic activity occurs. Revenues and profits recorded are merely digital entries—just a few numbers in a spreadsheet.

Wirecard’s reported cash thus ballooned impressively, supported by paper confirmations from fictitious partner entities. But unlike actual cash, this "digital cash" couldn’t pay the bills, fund growth, or repay debt—it existed solely in fantasy spreadsheets and auditor presentations.

Wirecard managed this charade successfully for years. After all, as long as auditors didn’t dig too deeply—and banks and regulators didn’t ask uncomfortable questions—no one would discover the truth.

But reality eventually does knock. Starting in 2015, financial journalists from the Financial Times (FT) started asking uncomfortable questions—questions Wirecard answered with indignant denials, defamation lawsuits, and accusations of market manipulation. The FT’s Dan McCrum, labeled by Wirecard as some sort of financial terrorist, kept digging anyway

In 2020, KPMG performed an independent forensic investigation. Their report effectively shattered Wirecard’s carefully constructed illusion, openly stating they could not verify that the “third-party” revenues even existed. Auditors at EY, forced to finally verify the cash held by partners, found nothing but blank stares and empty accounts. The jig was up. Wirecard’s stock collapsed, management resigned (or fled), and the company filed for insolvency in June 2020. Here all the timeline.

Irony: Germany’s pride, Germany’s embarrassment

It’s particularly ironic that Wirecard, once proudly touted as Germany’s great fintech success story—a symbol of the nation’s innovative power and financial sophistication—ended up the nation’s largest corporate scandal. A German member of the DAX 30, regulated by BaFin (Germany’s financial watchdog), and audited by prestigious EY, managed to deceive everyone for years. It took skeptical journalists, persistent short-sellers, and eventually a forensic audit to expose a fraud so blatant that in hindsight it seems laughable it lasted so long.

Perhaps the greatest irony of all? Wirecard’s elaborate structure of fake partners and fictional transactions was ultimately far less sophisticated than it appeared. The complexity wasn’t a brilliant corporate strategy—it was camouflage, a smokescreen to mask the painfully obvious fact that no money was coming in the door.

Red flags investors missed (or ignored)

Wirecard’s collapse, like Pescanova’s, didn’t come without warning signs. Investors who bought into the "unstoppable growth" narrative missed several glaring red flags:

Opaque revenues: Wirecard’s largest revenues came from third-party partners that no one had heard of, located conveniently in jurisdictions far from scrutiny. If a major chunk of your revenues comes from "Mr. Unknown" in Dubai or Manila, skepticism is probably warranted.

Massive cash balances, little cash flow: Wirecard reported billions of euros in cash—but regularly raised new debt. Genuine cash-rich companies rarely need emergency loans.

Aggressive pushback against critics: Wirecard’s extreme reaction to criticism—lawsuits, public attacks on journalists, claims of conspiracies—should have signaled something. Legitimate companies rarely go to war against transparency.

From an investor perspective, the key lesson of Wirecard is simple yet powerful: cash on a balance sheet doesn’t equal cash in reality. Revenues in an income statement aren’t automatically economic reality either. Always, always verify cash generation with the cash flow statement. Revenues can be faked, EBITDA can be manipulated, but actual cash hitting bank accounts is much harder to fabricate sustainably.

Wirecard also reminds us that complexity is not a hallmark of brilliance. It’s often a red flag. Companies that grow rapidly through unclear or complicated affiliate structures, particularly those operating in distant jurisdictions with limited oversight, demand deeper scrutiny, not blind admiration.

IV. The pattern behind the curtain – and the price of not looking

So what do a Galician seafood empire and a Bavarian fintech unicorn have in common—aside from both eventually filing for insolvency and becoming cautionary tales for the ages?

Surprisingly, quite a lot.

Pescanova and Wirecard operated in totally different industries, under different business models, and in different regulatory environments. But when you peel back the industries and look purely at the accounting mechanics, they were reading from the same playbook. Same tricks. Same incentives. Same tragic ending.

Both companies created sprawling webs of subsidiaries, affiliates, and mysterious “partners.” In both cases, complexity wasn’t an accident—it was a feature. This is your first warning sign as an investor: when you can’t follow the ownership structure without a map, a compass, and a stiff drink, something’s usually off.

The further away the transactions occur—geographically, structurally, or legally—the harder they are to verify. The illusion is simple: “Don’t worry about what’s over there—it’s all under control.” Except it’s not. And when investors accept that line without digging deeper, they become co-authors of their own deception.

Finally, let’s be clear: some companies are complex because their operations demand it. Multinationals, conglomerates, and diversified groups are naturally hard to untangle. But complexity can also be a defense mechanism. When the numbers don’t add up, management often blames it on “nuance” or “structure.” And investors, not wanting to look ignorant, nod along.

But here’s a hard truth: when you don’t understand a company’s financials, that’s not always a you problem. Sometimes, it’s because the company doesn’t want to be understood. As the saying goes, if you can’t see where the profits are coming from, chances are—they aren’t.

To be clear: not every company using the equity method or full consolidation is trying to fool you. These are normal, necessary accounting tools. But they are also the very tools most often misused when companies do want to fool you.

So read the footnotes. Trace the ownership tree. Compare net income to cash flow. Ask who the counterparties are. And when a company proudly waves around its EBITDA while carefully omitting how much of that cash actually belongs to shareholders—raise an eyebrow.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

🙌

Great research, great study cases! Appreciate it, thank you Javier! Cheers!