#79 Printing Money does not "always" Cause Inflation

How the Swiss National Bank Defies Economic Orthodoxy

If there’s one thing we’ve been told over and over again, it’s that printing money leads straight to inflation. It’s supposed to be as inevitable as gravity—more money floating around means prices must go up. End of discussion.

Except… what if it’s not?

Look at Switzerland. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) has been printing money like crazy for over a decade—quadrupling the amount of Swiss francs in circulation—and yet inflation has been practically nonexistent. Meanwhile, in the US and Europe, central banks have also been printing money, but they’ve ended up with inflation rates hitting multi-decade highs. So what gives?

If printing money always led to inflation, Switzerland should be drowning in it. But it’s not. Instead, the SNB has been casually hoarding foreign assets like a hedge fund while keeping the Swiss franc stronger than ever. It’s as if they read the central banking rulebook and thought, “Nah, let’s do the exact opposite.”

This raises an uncomfortable question: could it be that our beloved economic theories about money printing and inflation… aren’t always right?

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

1. Understanding the Basics: Why Printing Money Should Create Inflation

Alright, let’s start with the textbook version.

You print money, people have more to spend, but the amount of goods and services stays the same. What happens? Prices go up. That’s inflation 101. It’s why hyperinflation horror stories always start with a government cranking up the money printer to cover its debts. Before you know it, people are hauling wheelbarrows of cash just to buy a loaf of bread. Classic.

Take Weimar Germany in the 1920s. The government printed so many marks to pay off war debts that prices doubled every few days. By the end, kids were playing with stacks of cash because it was cheaper than buying toys. Or Zimbabwe in the 2000s—banknotes with trillions printed on them, all worth less than a bus ticket.

The theory is simple: when there’s too much money chasing too few goods, money loses its value, and prices spiral out of control. That’s why central banks are supposed to be careful with how much money they create. And yet… Switzerland prints money like it’s going out of style and doesn’t have this problem.

So what’s different? Either the Swiss are using some kind of economic witchcraft, or there’s more to this inflation story than we’ve been told. Spoiler alert: it’s the second one.

2. The Swiss Exception: A Central Bank That Prints Money Without Price Surges

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) has been printing francs like crazy for over a decade—its balance sheet is bigger than Switzerland’s entire GDP. Yet, inflation in Switzerland has remained ridiculously low, often below 1%. In fact, for years, the real problem wasn’t inflation—it was deflation (aka falling prices, the thing central banks usually panic about).

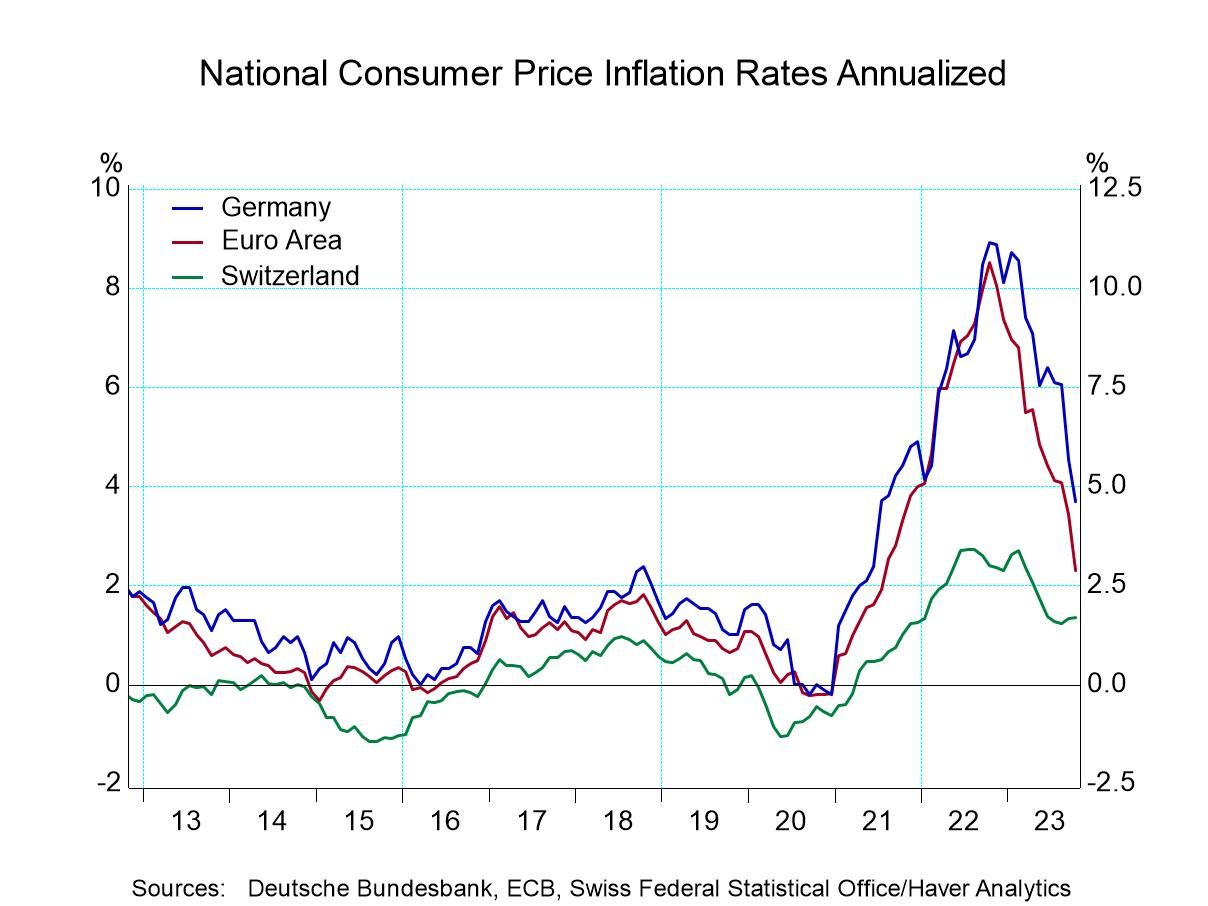

Meanwhile, in the US and Europe, the Fed and the ECB also went on a money-printing spree, and surprise, surprise—inflation shot through the roof. In 2022, US inflation hit a 40-year high. The eurozone wasn’t much better. And yet, in Switzerland? A peak of 3.5% inflation, and now it’s back below 2%.

How is this possible? What is the SNB doing that the Fed and ECB aren’t? Do Swiss francs have magical anti-inflation properties? Not quite. But the SNB does something that almost no other central bank does: instead of using its freshly printed money to buy government debt, it buys foreign assets—stocks, bonds, even gold.

That’s right. While the Fed and ECB spend trillions propping up their own governments, the SNB is out there buying shares of Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon like an overfunded hedge fund. Imagine the Federal Reserve announcing, “We just bought $100 billion in Tesla stock.” That would be complete chaos. But in Switzerland, it’s just another Tuesday.

The result? While other central banks print money backed by government IOUs (“I Owe You”), the SNB prints money backed by productive global assets. Instead of devaluing its currency, this strategy has made the Swiss franc stronger. In a world where central banks usually treat money printing like setting a house on fire, the SNB has somehow figured out how to do it without burning everything down.

But of course, no magic trick comes without risks. And if you think the SNB’s balance sheet is risk-free, well… we’ll get to that soon.

3. Comparing Central Banks: Debt-Backed vs. Asset-Backed Money Printing

Let’s play a game. Imagine you’re a central bank and you can print unlimited money. What do you do with it?

Option A: You lend it to your government by buying up its debt, ensuring politicians can keep spending without worrying too much about budget constraints.

Option B: You use it to buy stocks, foreign bonds, and gold, building a massive investment portfolio.

Most central banks—like the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB)—choose Option A. They print money and use it to buy government bonds (aka government debt). This keeps interest rates low and helps governments borrow more cheaply. The problem? It also means that the money they create is backed by… well, more debt.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB), on the other hand, goes for Option B. Instead of filling its balance sheet with Swiss government bonds (which, by the way, barely exist because Switzerland runs a tight fiscal ship), it fills it with foreign assets—US stocks, German bonds, even gold.

Let’s look at the numbers:

SNB: Balance sheet peaked at 135% of Switzerland’s GDP, made up largely of foreign assets (equities, foreign bonds, gold).

Federal Reserve (Fed): Balance sheet around 27% of US GDP, mostly US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

European Central Bank (ECB): Balance sheet around 50% of eurozone GDP, primarily euro-area government bonds and loans to banks.

Bank of Japan (BoJ): Balance sheet over 120% of Japan’s GDP, mostly Japanese government bonds, plus some domestic stocks (ETFs).

Visually, here’s the difference:

Fed/ECB/BoJ: Print money → Buy government debt → Support fiscal deficits → Risk devaluation & inflation.

SNB: Print money → Buy global assets → Strengthen currency → Inflation remains low.

The takeaway? Not all money printing is created equal. The Fed and ECB have essentially turned into enablers of government debt, while the SNB is running a strategy that looks more like sovereign wealth fund management than traditional central banking.

4. Why Doesn’t the Swiss Franc Collapse or Spark Inflation?

By now, you might be thinking: Wait, if the SNB is printing so much money, why doesn’t the Swiss franc collapse like every other currency that’s been overprinted? And why don’t Swiss prices go crazy?

Great questions. And the answers highlight why the SNB’s strategy is so different from the Fed or ECB’s.

4.1 The Swiss Franc Is a Global Safe-Haven Currency

The Swiss franc isn’t just another currency—it’s one of the most trusted in the world. When financial markets panic, investors rush to buy francs, treating them like a more sophisticated version of gold. Why? Because Switzerland has a rock-solid banking system, a government that actually balances its budget, and a history of keeping inflation low.

This means that every time there’s a crisis (think 2008, 2020, or any geopolitical mess), demand for Swiss francs increases. Normally, printing more money would reduce a currency’s value, but in Switzerland, the global demand for francs is so high that the SNB has to actively weaken its currency just to keep exports competitive.

Yes, you read that right. While most countries struggle to keep their currency from collapsing, Switzerland has the opposite problem—it has to keep the franc from getting too strong. That’s why the SNB printed so many francs in the first place: to buy foreign assets and weaken the currency so that Swiss businesses don’t get crushed by an overvalued franc.

4.2 Switzerland’s Economy Is Extremely Competitive

Even without the SNB’s interventions, Switzerland would still be in a strong position. It has:

One of the lowest tax rates in Europe, but far away from a tax heaven…

No capital gains tax, which attracts investors.

A budget surplus (unlike the US or EU, which run massive deficits).

A workforce that is highly skilled and 22% foreign-born (because everyone wants to work there).

All these factors keep the Swiss economy strong and ensure that, even with a massive SNB balance sheet, there’s no trust crisis in the currency.

So, No Risks? Not So Fast…

Of course, this doesn’t mean the SNB has figured out a risk-free way to print money. The strategy works as long as investors trust the Swiss franc and the global assets backing it keep performing well. But what happens if markets crash? Or if investors suddenly stop treating the Swiss franc as a safe haven?

5. The Hidden Risks: Could Switzerland’s Strategy Backfire?

5.1 The SNB’s Massive Stockpile of Foreign Assets Is a Double-Edged Sword

The SNB owns a gigantic portfolio of global stocks and bonds. This works beautifully when markets are going up. In the good years, the SNB makes billions in profits just from asset price appreciation and dividends.

But what happens when markets tank?

We already got a taste of this in 2022, when the SNB reported a record-breaking loss of CHF 132 billion—yes, billion. That’s about 18% of Switzerland’s GDP wiped out in a single year. The culprits? A sharp decline in global stock and bond prices, combined with a stronger Swiss franc reducing the value of its foreign holdings.

This loss was so big that the SNB had to cancel its usual payout to the Swiss government and cantons. Imagine running a country where your central bank sends you a big fat check every year—until suddenly, it doesn’t. That’s what happened in Switzerland, and let’s just say that Swiss politicians weren’t too thrilled.

5.2 The Swiss Franc’s Strength Could Backfire

Another paradox of the SNB’s strategy is that while it has spent years trying to weaken the Swiss franc, it also relies on the franc being a safe-haven currency.

But what if the SNB ever needs to sell a chunk of its foreign assets to cover losses? That would mean converting its foreign holdings back into francs—driving up demand for the Swiss currency and making it even stronger. In an extreme scenario, the franc could appreciate so much that it crushes Swiss exports, slows economic growth, and sends the country into recession.

Think about it:

The SNB prints money → buys foreign assets → keeps the franc weaker.

But if it sells those assets to cover losses → demand for francs spikes → the currency gets stronger instead.

It’s a delicate balancing act, and while the SNB has handled it well so far, it’s not bulletproof.

5.3 The Risk of Political Pressure

For years, the SNB’s profits made it a national treasure. Swiss politicians loved the annual payouts from the central bank. Some politicians even wanted to distribute part of the SNB’s stockpile directly to Swiss citizens. There were proposals to distribute part of the SNB’s accumulated wealth as a direct cash payment to citizens. Given Switzerland’s reputation for fiscal prudence, referendums, and direct democracy, this would have been the ultimate Swiss move—letting citizens vote on whether they should get a payout from the central bank.

But after the massive loss in 2022, that narrative changed. Suddenly, people were asking:

Should the SNB really be investing so much in stocks?

What happens if it can’t pay out to the government for multiple years?

Should the SNB be forced to reduce risk and change its strategy?

If political pressure builds, the SNB might be forced to adjust its investment approach—which could disrupt the very system that has worked so well for Switzerland.

Can This Strategy Work Forever?

The SNB’s approach to money printing has been a massive success—until it wasn’t. While it has avoided inflation, it has introduced new kinds of risk that other central banks don’t have.

As long as global markets stay strong and the Swiss franc remains a safe-haven currency, the SNB’s model works. But if either of those things change, the Swiss central bank could find itself in a very tough spot.

6. Lessons for Investors

Lesson 1: Not All Money Printing Is Equal

The problem with the Fed and ECB is that they print money to fund government deficits, which means the money is used for spending, subsidies, and political promises that don’t necessarily generate value. The SNB, on the other hand, invests in productive assets—stocks, bonds, gold—creating a capitalized balance sheet instead of a debt-backed one.

If you had to choose between being backed by an Apple share or by, say, Italian government bonds, which would you trust more? Exactly.

Lesson 2: You Can’t Print Your Way Out of Bad Policy

One reason the SNB gets away with its strategy is that Switzerland is fundamentally well-run.

Low government debt. Unlike the US or Eurozone, Switzerland doesn’t need its central bank to bail out a bloated public sector.

Competitive economy. Low taxes, skilled workforce, stable legal system—this attracts capital instead of repelling it.

The Swiss franc is a global safe haven. That means investors actually want Swiss francs, even when the SNB prints more of them.

Now, imagine trying this in Venezuela. If the Venezuela central bank printed Bolivars to buy Tesla shares, would investors suddenly trust the Bolivar? Of course not. The government would probably find a way to mess it up, and hyperinflation would follow anyway.

Moral of the story? The SNB’s strategy works because Switzerland is Switzerland—not because printing money is some magic trick.

Lesson 3: Other Central Banks Could Try It—But Should They?

Could the Fed or ECB follow the SNB’s lead and start buying stocks instead of just government debt? Technically, yes. Some people have even suggested that central banks should start investing in index funds instead of just bonds.

But here’s the problem: politics.

Imagine if the Fed started buying Microsoft or Google shares. The political backlash would be insane. Who decides which stocks to buy? What happens if those stocks crash?

The ECB can barely get agreement on interest rates—now imagine it trying to pick stocks that benefit all eurozone countries equally. Good luck with that.

The SNB operates independently and doesn’t have to deal with the same political headaches as the Fed or ECB. That’s a huge advantage.

So while it’s theoretically possible for other central banks to copy this strategy, in reality, it’s just not practical in most places.

So, is Switzerland proof that central banks can print money responsibly? Maybe. Or maybe it’s just a high-stakes balancing act that hasn’t collapsed yet.

The real question is: Would you trust your central bank to pull off the same trick?

For most countries, the answer is probably no.

At the end of the day, the SNB’s approach proves that money printing is not the enemy—bad money printing is. It’s not about the quantity of money, but the quality of the balance sheet behind it.

So, next time someone tells you that printing money always causes inflation, tell them about Switzerland. Just don’t forget to mention the risks—because even the best central bank in the world can’t defy reality forever.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

Never thought about these scenarios. Thanks for making us think in different direction.

Interesting. Depends on stocks they invest in. Investing in SP500 at the moment is probably not the best idea for the central bank