#73 Psychological Moonshots

Incremental/radical technological innovation vs traditional industries. Capital investments, continuous disruption risks. Influence on valuation. Phycho advances creating incremental switching costs.

If moonshots can promise a 10-fold impact on our world, why do so few companies dare to pursue such ambitious goals? How does the innovator's dilemma influence their choices? And how do these strategic considerations shape market expectations and, ultimately, the valuation of various types of companies?

In today’s article, we dive into these questions and shine a spotlight on an often overlooked but immensely powerful aspect of innovation. This facet, when executed properly over long periods of time, can drive the widening of a moat without the hefty price tag of massive capital investments.

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

Incremental innovation refers to improvements or modifications to existing products, services, or processes. The focus here is on optimizing and refining what already exists, making small enhancements that, over time, can add up to significant benefits—whether by reducing manufacturing costs, improving functionality, or enhancing user experience. This type of innovation is the most common and is seen daily in countless products and services around us. In contrast, radical innovation involves groundbreaking changes that redefine markets or create entirely new ones. These innovations aim for outcomes that are ten times greater in impact, rather than merely a 10% improvement. We can think of diverse historical examples such as the invention of the steam engine, the radio, Ford's assembly line in the last century, the development of the Internet, or the recent emergence of OpenAI's ChatGPT.

It’s notable that most of these revolutions don't come from the dominant companies or the most resource-rich entities like governments. Large R&D departments are often disrupted by small entities with limited resources. Why is this?

Challenges for Large Organizations

The innovator's dilemma is a key concept explaining why large, established companies often hit a wall when it comes to radical or disruptive innovation. This dilemma occurs because organizations, focused on maintaining short-term profitability and meeting the needs of their current customers, often fail to adopt new technologies or business models that could eventually displace them. A clear and recent example is Google's apparent difficulty in launching something as "simple" as OpenAI's ChatGPT. Despite being a leader in the industry and supposedly the most advanced company in AI research, Google has repeatedly failed in its recent product launches.

Two main problems come into conflict for a giant like Google:

It’s an Harakiri: Launching a disruptive product like ChatGPT directly attacks Google's incredibly profitable core business model. While it’s easy to criticize from the outside, this move could potentially harm their primary revenue source. If it were your business, you might hesitate too.

Reputation Risks: Google has a reputation to protect and cannot afford to release a product that might make significant errors and damage its image. Bard, Google's AI assistant, faced infinite criticism for fabricated responses (setting aside any critique of its perceived "woke" biases). Simply put, Google cannot (or should have not) afford to give wrong answers—it’s intolerable. On the other hand, OpenAI didn’t face these same limitations. As a nearly startup (at the time), OpenAI created a disruptive and initially free product. Does it make mistakes occasionally? Sure, but that’s acceptable for them, and for us, clients.

Lastly, size matters. Structural barriers also play a crucial role in a large company’s ability to adopt disruptive innovations. Bureaucracy and a lack of agility prevent the quick adoption of innovative ideas. In Google's case, its organizational structure has often been criticized for being too complex, slow, and many other issues that we all know well.

Furthermore, Google has had a division for decades dedicated to experimental projects, known for its "moonshots." These are extremely ambitious projects with the potential to significantly change the world. The mission of Google X is to tackle complex problems with innovative solutions, such as self-driving cars aimed at reducing traffic fatalities by 90% or smart contact lenses that monitor glucose levels. Despite their high potential, none of these projects have achieved significant success that we remember.

I don't mean to single out Google negatively in this article. They have countless products and services that we’ve all used, and keep using, over the years. However, this highlights why keeping an organization at the forefront is incredibly challenging and often underestimated by us, investors, sitting comfortably analyzing the business results of this or that company. Maintaining a company with hundreds of thousands of employees on a path of growth and innovation, while correctly incentivizing thousands of workers, is a feat achievable by very few. It's not the norm; it's the rarest of exceptions.

Obviously, these problems are not exclusive to Google. Not too far away, Meta has been pouring billions and billions into their new vision of the metaverse (is it still called like that?).

How shall then we value these Moonshot Projects? The truth is valuation of moonshot projects often depends entirely on the current market sentiment. Periods of technological disruption are frequently accompanied by stock market bubbles. These bubbles are mostly recognized only in hindsight. You can rarely be sure you are living through one (with a few exceptions). For instance, the dot-com bubble of the 2000s was characterized by many worthless companies with absurd valuations selling empty promises. Yet, the wave of innovation that the bubble rode on was real. The Internet changed the world. Today, we’re experiencing a similar wave with AI. Is it a bubble? Honestly, who knows. Will AI progress as we hope or expect? Will we achieve full autonomous driving in just a few months? Will Tesla’s robots replace physical labor?

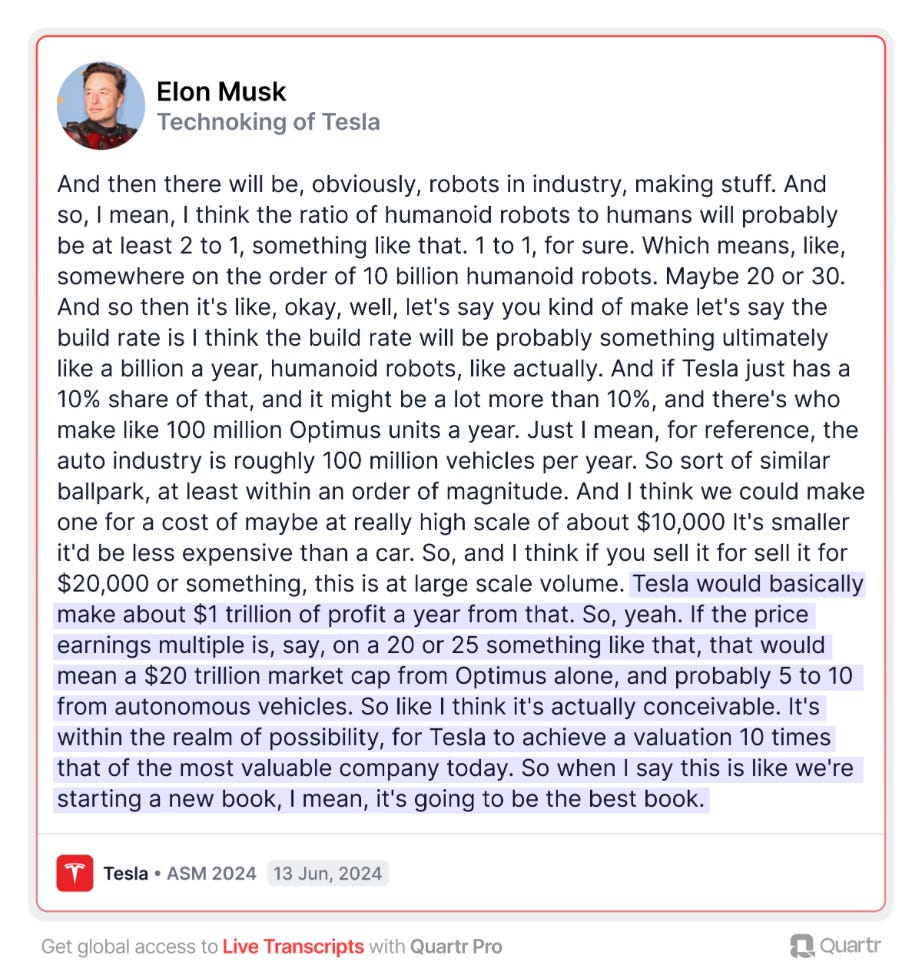

How do we create a DCF model for the sales and margins of Tesla’s AI-Powered Robot (Optimus)? How can we estimate the demand? How do we know Tesla will be the winner?

The answer, as is often the case, lies with management. When investing in innovative companies, you must account for the fact that many things will go wrong. But you must ensure that the company is special and, more importantly, that the leaders are exceptional. Elon Musk could a prime example. Despite the numerous setbacks and controversies, Musk has consistently demonstrated visionary leadership and the ability to push the boundaries of what’s possible. His relentless drive and ability to execute on bold ideas, from revolutionizing EV with Tesla to what he has achieved with SpaceX, highlight why leadership matters immensely in navigating the unpredictable terrain of innovation.

The math checks out. Is it realistic? I leave it to each of you.

Given these challenges (or perhaps because they are insurmountable), it’s no surprise that many traditional investors have tended to avoid sectors subjected to continuous disruptive innovation. The reason is simple: it’s incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to predict future cash flows and understand the returns on investments in such volatile environments. Often, it might not even be worth the effort. It’s much easier to value a company that isn’t constantly subject to innovation or disruption.

Consider companies like the Spanish Vidrala or French Verallia, both major producers of glass packaging for beverages and food products. These are seemingly boring businesses with significant capital requirements but also have inherent advantages similar to those of the concrete industry. Their economic profile and capital return characteristics are relatively straightforward to predict after any management decision. For instance, if they open a new manufacturing site in a region, you can fairly estimate the impact on their financials. The predictability and stability of such companies make them more attractive to some investors who prefer certainty over the excitement (and risk) of investing in cutting-edge technology sectors.

The same logic applies to other defensive companies, such as those in the consumer staples sector or food retailers. These defensive businesses are often valued at market premiums due to their predictability, although they frequently lack significant real growth.

In contrast, technology companies, at least the reputable ones, tend to trade at high multiples—not because of their predictability, but due to their potential for substantial growth. Outsized returns are definitely achievable in this sector; just look at the performance of the Nasdaq in recent years. The critical question to ponder is: Are these risk/reward scenarios fully priced in, or not? Based on recent years' performance, one might think the answer is clear. But what about the future?

I understand that these points can be quite controversial, but I'm curious—how do you approach these dilemmas? What do you look for to gain confidence in the future? How do you identify the winner in a given field? Additionally, what strategies can a large company employ to overcome the innovator's dilemma and continue fostering new innovations?

The Power of Psychological Moonshots

Rory Sutherland wrote already in 2019:

The argument for Google X is that the major advances in human civilisation have come from things that, rather than resulting in modest improvement, were game-changers – steam power versus horse power, train versus canal, electricity versus gaslight. I hope X is successful but think that their engineers will find it difficult. We are now, in many cases, competing with the laws of physics. The scramjet or the hyperloop might be potential moonshots, but making land- or air-travel-speeds so much faster is a really hard problem – and comes with unforeseen dangers.

By contrast, I think ‘psychological moonshots’ are comparatively easy. Making a train journey 20 per cent faster might cost hundreds of millions, but making it 20 per cent more enjoyable may cost almost nothing.

It seems likely that the biggest progress in the next 50 years may come not from improvements in technology but in psychology and design thinking. Put simply, it’s easy to achieve massive improvements in perception at a fraction of the cost of equivalent improvements in reality. Logic tends to rule out magical improvements of this kind, but psycho-logic doesn’t. We are wrong about psychology to a far greater degree than we are about physics, so there is more scope for improvement. Also, we have a culture that prizes measuring things over understanding people, and hence is disproportionately weak at both seeking and recognising psychological answers.

The concept behind psychological “moonshots” may seem straightforward at first glance, but it carries profound implications. Instead of seeking costly and complex solutions to technical problems, this approach focuses on finding innovative ways to significantly alter user perception and experience. By concentrating on how people feel and behave, these innovations can offer benefits comparable to major technological advances but with comparatively negligible investments. From a financial perspective, this translates to projects that require minimal capital expenditure yet yield exceptionally high incremental returns on capital—essentially, the holy grail for investors.

A prime example of a psychological moonshot is Uber’s real-time car location feature. This simple addition doesn’t reduce the actual waiting time for a taxi, but it makes the wait much less frustrating. The idea stemmed from a keen observation by Uber’s founders: the uncertainty of not knowing when the car would arrive was far more irritating for users than the wait time itself. By showing the car’s progress on a map, Uber transformed the waiting experience, making it seem shorter and more manageable.

However, the question every savvy investor should ask is: Has this innovation created a competitive advantage? How difficult is it for a competitor to replicate this feature? On the surface, it appears to be a significant user enhancement, but one that is easily replicable.

In contrast, let’s compare this with the impact of Apple’s seamless ecosystem integration. The first time you experience how a Mac integrates with an iPhone or an older Mac, even the most skeptical observer might find themselves saying, “Wow.”

Since Steve Jobs' passing, Apple has faced continuous criticism for its perceived lack of innovation. While it’s true that radical innovation has avoided Cupertino’s company, it’s equally true that Apple has continued its path of incremental innovation—demonstrated by its development of in-house chips and new products. More importantly, Apple has excelled in psychological moonshots.

This type of device integration is virtually impossible for a competitor to replicate. Firstly, few companies have such a wide range of product categories and deep market penetration. It's no secret that once you enter the world of Apple products, it’s challenging to leave—and often, it's due to sheer convenience.

Apple has strategically distanced itself, perhaps wisely, from the pursuit of moonshot innovations that many large companies struggle to achieve. Instead, it has crafted a cohesive and appealing ecosystem that keeps its users deeply engaged and loyal. Isn’t this the clear definition of competitive advantage? Moreover, consider the capital required to achieve these advantages. It seems that Apple was one of the pioneers and strongest advocates of leveraging the power of psychological moonshots long before the term became popular.

To conclude, it's important to emphasize that the concept of “psychological moonshots” shouldn't be viewed solely from the perspective of tech giants like Apple. I use Apple as an example because it’s well-known and easy for everyone to understand. However, this approach is applicable at various levels and also to much smaller companies.

Recently, we came across a small Japanese company that perfectly illustrates how a simple solution can have a significant impact. This company, born as a spin-off from a larger organization, has developed an API that centralizes the entire indirect procurement process within a company.

Traditionally, large organizations face significant challenges when trying to centralize their procurement processes. This solution centralizes purchasing while allowing each department the flexibility to choose and buy exactly what it needs. It achieves this by comparing prices across a virtually endless number of suppliers, leveraging the company’s scale to its fullest advantage without sacrificing the autonomy of individual departments.

This approach not only enhances efficiency and reduces costs but also facilitates greater transparency in the procurement process. Moreover, by integrating with existing ERP systems, this solution creates significant switching costs. These costs encourage large companies to adopt and maintain the technology, as it becomes deeply integrated with their operations and management systems.

This example demonstrates that “psychological moonshots” are not reserved exclusively for large tech corporations. By focusing on solving real problems in innovative ways and leveraging user psychology, even small companies can create products and services that not only enhance customer experience but also generate substantial competitive advantages.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

gracias!