#76 The 4th Symphony of the Empire Builder

What Brad Jacobs Teaches Us About Breaking Bias and Building Billion-Dollar Companies

We all have our preferences when investing—certain leadership styles, types of companies or strategies we favor. And when a CEO or business doesn’t fit into those boxes, we’re quick to dismiss them. Brad Jacobs is one of those CEOs who, at first glance, raises a lot of red flags. His aggressive approach to acquisitions, reliance on multiple arbitrage, and close connections with investment bankers or consulting firms like McKinsey are the kind of things that would normally make me turn the other way.

But here’s the thing: Jacobs has built several wildly successful companies over decades. His results speak for themselves, forcing me to question my own biases. Jacobs’ story is a reminder that just because a strategy doesn’t align with our personal philosophies doesn’t mean it’s doomed to fail. In fact, his success is a lesson in staying open-minded, particularly when assessing leaders and investment opportunities that don’t fit the usual mold.

In his book “How to Make a Few Billion Dollars,” Jacobs outlines the principles and strategies that have guided him through decades of building value in his companies. Let’s take a closer look at his approach and what we can learn from it.

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

Brad Jacobs by Brad Jacobs

I’m a career CEO with a unique track record as a Wall Street moneymaker. I’ve founded eight billion-dollar or multibillion-dollar companies, creating tens of billions of dollars of value for shareholders across multiple industries. This includes six publicly traded corporations: United Waste Systems, Inc.; United Rentals, Inc.; XPO, Inc.; GXO Logistics, Inc.; RXO, Inc.; and my new company, QXO, Inc.

QXO will consolidate the building products distribution industry, which is large, growing, and rich with acquisition opportunities. Building products distribution has approximately $800 billion in annual revenue between North American and Europe. Our strategy is to create a tech-forward industry leader through accretive M&A and organic growth.

My goal with QXO, as with all my ventures, is to generate outsized value for shareholders. My edge is that I hire exceptionally talented people who think big and are committed to achieving remarkable results. My teams and I have completed about 500 M&A transactions across multiple industries, and we’ve raised approximately $40 billion of debt and equity capital, including three IPOs.

In the supply chain industry, we grew XPO into a top ten global logistics provider, and then completed a $7 billion spin-off of GXO Logistics and a $5 billion spin-off of RXO, creating two new public companies in about 15 months. XPO was the seventh best-performing stock of the last decade in the Fortune 500 and became a "32-bagger" — initial investors in XPO made more than 32 times their money.

Prior to XPO, I founded United Rentals and United Waste Systems. We built United Rentals into the largest construction equipment rental company in the world in 13 months. United Rentals was the sixth best-performing Fortune 500 stock of the last decade and became more than a “150-bagger” — the share price at inception was $3.50 and its stock now trades at well over 150 times that price. United Waste’s stock outperformed the S&P 500 by 5.6 times from the time I took the company public to the time we sold it for $2.5 billion.

Something he does not say here is that he studied piano and mathematics at Brown University before dropping out. Sounds a bit like an outsider…

As an investor, it’s easy to be skeptical of CEOs who pursue growth through aggressive M&A, as it often leads to over-leveraging or unsustainable business models. Jacobs’ reliance on this method and his focus on integration strategies through multiple arbitrage could have easily made me turn away. But here’s where we must recognize our biases and should remain open minded: Jacobs succeeded because he approached these acquisitions with precision and discipline. His ability to integrate businesses and create value through severe cost-cutting and organizational restructuring is not luck—it’s a carefully honed skill as we are seeing below.

1. Value Creation and Overcoming Challenges

Problems are assets where to skeeze value

“At one memorable lunch, I arrived burdened with problems that I began to unload on him. Mr. Jesselson listened carefully—he was good at that—and waited until I had run out my string. Then he put down his fork, turned to me, and in his thick German accent said, “Look, Brad, if you want to make money in the business world, you need to get used to problems, because that’s what business is. It’s actually about finding problems, embracing and even enjoying them—because each problem is an opportunity to remove an obstacle and get closer to success.

Life can be uncomfortable, but you can accomplish a lot if you can figure out how to reframe the uncomfortable things in ways that allow you to utilize them.

In that moment, I learned something invaluable: Problems are an asset—not something to avoid but something to run toward. Big ambitions often beget even bigger problems. If your initial reaction to a major setback is overwhelming frustration, that’s understandable, but it’s also counterproductive. Once you’re over that moment, pivot toward success: “Great! This is an opportunity for me to create a lot of value.

The fact is, you're not going to create a huge amount of value unless you're courageous, and problems are the by-product of risk. As long as you're honest with yourself, recognize mistakes as soon as they surface, and course-correct with no ego, the things about your business that aren’t good can become great.

Tackle it head-on: Where are the inefficiencies in the process that created this problem? Where can my team reduce operational defects with Lean Six Sigma? Do I have the right people in place in key positions?

Embrace everything that comes your way, the good and especially the bad. And don’t just accept adversity—figure out how to capitalize on it.

In the four decades since that lunch with Mr. Jesselson, I’ve dealt with nearly every problem you can imagine, a fair number of which were self-inflicted: challenges with acquisitions, people, tech, branding, you name it. I’m not surprised when things don’t go perfectly, because that’s the nature of this universe we live in. The big gunky problems—existential threats that are not yet terminal—can be where the best opportunities lie.”

If you want to earn huge, you need to think huge. Your goals should be bigger than what you currently think you can accomplish, because that can actually help you achieve those goals. Picture what success will look like for you, and be specific. You want to make a lot of money, sure. But exactly how much money do you want to make? By when? How will you feel when you have all that money in hand? What will you spend it on? Invest in? Donate to? Whose lives will you improve? If I had tried to do everything I wanted to, I never would have accomplished anything big. Narrow your focus to your most important dreams and tune out everything else.”

The short report

“That happened dramatically in our case. The “short” report was packed with a lot of baloney, but of course the market acted first and analyzed later and our stock price went into free fall, down 26 percent in one day. Of course, the short-seller cashed in.

Companies handle short-seller attacks in different ways. Some have gone to ground and stopped taking calls when short-sellers attack. Others have tried to stoically ride it out, or complain through the media, only to make matters worse. Not us. We did exactly what I’ve been describing in this chapter. Instead of snarling back at the short-sellers, we concentrated on the situation at hand without judging what had happened to us. We knew that we had to radically accept the circumstances as they stood, before we could arrive at a solution.

The “short” report was all over the financial media the morning of December 18, 2018. Fortuitously, I was already hosting a number of fund managers at my house that night for dinner, as well as a few people from my team. That included Matt Fassler, our new chief strategy officer at the time. Matt had just joined us the prior week after two decades as a top analyst at Goldman Sachs, and the dinner was to introduce him to some of our institutional investors. Now there was no question what topic would dominate the conversation that evening.

In theory, this should have been an unsettling prospect—new hire, big stock dive, savvy dinner crowd. Our C-suite spent five hours in a conference room that afternoon going over the “short” report page by page, unraveling its arcana, identifying the many places where the data had been twisted. When Matt arrived at my home that evening for dinner, he had his arms around every nuance of the issue. Whatever concerns about XPO’s long-term health that existed at the beginning of dinner were gone by dessert.

The next day at an investor conference in Boston, a preplanned lunch became an impromptu Q&A firing squad about the short-seller attack on our stock. We were peppered with incomings as the sit-down began, but by the time we got back to our Connecticut headquarters that afternoon, the part of the investment community we care about most—the long-term holders—were climbing back on board.

That was the pivotal moment of the entire saga. The short-seller crisis had made our stock extremely cheap, and instead of fixating on that as bad, we focused on achieving a good outcome. From that perspective, the share price was manna from heaven, and we decided to buy back $2 billion worth of our stock.

Our bankers didn’t see it that way. “Two billion dollars?” they said, aghast. “That’s too high a percentage of your market cap. No one’s ever done something like that. Why don’t you buy a far smaller amount, like $100 million to $200 million?

The bankers had a point from where they were sitting. The high-yield bond market was in the pits. We would have to take out a short-term “bridge” loan to do the buyback at the scale we were envisioning, and we knew that bridge loans had sunk more than one enterprise. But by then, we were thinking bigger than the banks. Just because we were the first company to buy back such a high percentage of our stock in a similar situation didn’t mean it was a bad idea. In fact, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

With data in hand and conviction on our side, I called two board meetings to make sure our directors were fully informed of the “short” report’s contents and its many factual distortions. I assured everyone that our communications, investor-relations, and corporate strategy teams were on top of everything. I also relayed our bankers’ verdict that any significant stock buyback plan would be ill-advised and followed this with our recommendation to throw deep and buy big. It was a challenging fiduciary situation, and the board spent hours discussing the pros and cons of different approaches. By late afternoon, the directors had approved a buyback of $2 billion of XPO shares.

This story illustrates the high-impact, real-world benefits of rearranging your brain. Everything I just described happened within 48 hours of the “short” report first going public. A couple of years later, those $2 billion of shares we bought back ended up being worth $6 billion—a $4 billion profit. As an added bonus, the high-yield bond market recovered in fairly short order, so we were able to close out the bridge loan and shift the debt burden to the bond market, where it belonged.”

My take:

Brad Jacobs deals with challenges in a way that many investors can learn from. Instead of seeing problems as something to avoid, he views them as opportunities. This is a huge difference between entrepreneurs and managers and a big shift from how most investors typically react—often treating challenges as warnings to pull out. Jacobs believes that problems are just part of doing business, and by addressing them directly, you can actually find ways to create value.

When Jacobs faced a short-seller attack, a situation that would normally cause most companies to go on the defensive, he stayed focused and saw it as an opportunity to buy back stock at a bargain price. Instead of getting emotional or defensive, he stuck to the facts and ended up turning that tough moment into a huge win—a $4 billion profit. His approach reminds us that the right attitude and clear strategy can turn setbacks into gains, but this only works if you have a management team that’s honest and willing to push through the tough parts.

This ties directly into the importance of setting clear, measurable goals. We normally believe, and want to see, companies aiming for something specific—like achieving a 15% operating margin—. We believe that in most of the cases, if they don’t have a particular target then they will never push yourself to figure out how to reach it. Setting goals isn’t just about ambition, it’s about creating accountability. Without targets, you can’t evaluate management or assess whether progress is being made. And more importantly, without clear goals, no one will push themselves to perform at a high level.

Some successful companies don’t hold public calls or announce specific targets, and that’s fine. But there’s a big difference between keeping goals private and not having goals at all. If there are no clear objectives, there’s nothing to measure performance against, which leads to a lack of accountability. And when people don’t have goals to meet, there’s no urgency or drive to push harder and do better.

2. Leadership and imperfect information

“Successful people are self-aware enough to avoid the following three impediments to effective leadership:

The belief that you’re right, no matter what. “I absolutely know the answer, and I’m not going to change my mind, even if new evidence comes to light.” Rigid thinking like this doesn’t cut it. I say that from my own experience, because business at the level where I like to operate is marked by constant turbulence. I need to be able to zig and zag opportunistically, even if it requires completely rethinking a former premise. Being dialectical means looking at something from different perspectives and interpreting it in multiple ways that are all valid.

The belief that other people must hold the same opinions you do. You’ll want to implement strong feedback loops and a work culture where everyone accepts that there’s more than one valid way to look at an issue. We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress.

And lastly, the belief that every inch of a potential course of action must be analyzed before you act. This holds true whether it’s hiring or firing someone, doing a deal, raising capital, investing capex, or any other major decision. A CEO who waits for perfect terms and ideal conditions before acting creates corporate constipation. I critique myself on all high-value decisions, scanning constantly for prejudices that might be skewing my reasoning—but not to the point of procrastinating just because things are imperfect.”

“Sometimes I’m wrong when I think I’m right. So, I’m always ready to change my beliefs based on new information.”

My take:

One of the things that sets Brad Jacobs apart as a leader, and many other fenomenal leaders, is his willingness to admit when he’s wrong. In both business and investing, there’s a tendency to cling to initial ideas or decisions, even when new evidence shows they might be wrong. This rigidity can cause you to miss opportunities or, even worse, double down on bad calls. Jacobs doesn’t fall into this trap. He’s ready to adjust his course whenever new information comes to light, and that flexibility has been key to his long-term success.

Jacobs’ approach highlights a critical trait for any leader or investor—being adaptable. Industries are constantly changing, and sticking to a fixed mindset or a rigid plan is a recipe for getting left behind. Jacobs’ ability to “zig and zag” based on new circumstances is a reminder that staying open to change, even if it means rethinking your entire strategy, is one of the most valuable skills a leader can have.

Too often, investors (and entrepreneurs) can get stuck in a pattern of over-analysis, spending weeks or even months trying to find the smallest pieces of information to justify a decision they’ve already made. This type of bias only reinforces a decision that might no longer make sense. Jacobs avoids this by understanding that acting on imperfect information is better than waiting forever for perfect conditions that may never come.

Truly intelligent leaders, investors, and individuals are those who can recognize when they’ve been wrong, learn from it, and make changes accordingly. It’s not about stubbornly holding on to a belief; it’s about being wise enough to see when things have changed and being willing to admit it.

Intelligent or wise people are those who, after being proven wrong about something (or after receiving new arguments that refute their previous thoughts or knowledge), are able to reflect on it, learn more about the topic, and ultimately change their mind and recognize they were wrong.

3. Getting the Major Trend Right

“One of the most valuable pieces of advice I received from my mentor, Ludwig Jesselson, is, “You can mess up a lot of things in business and still do well as long as you get the big trend right.” I’ve taken his words to heart, and with each new company I start, I make sure I understand the major trends that could threaten the business or help it soar.

I’m obsessive when learning about an industry, and trendspotting is a big part of that process. I discovered early in my career that tech is always a consideration in one form or another, sometimes dramatically so. As a result, a great deal of my success has come from innovating traditional business practices, whether it’s through automation, robotics, data science, or information sharing.

One of the first things I look for in an industry is scalability. I want to be able to envision how I’ll take a business from a few million dollars to tens of billions of dollars. What will be the path to do that, and how fast can we move along that path? Is the industry growing much faster than GDP so that we’ll probably generate top-line growth each year just by showing up and can build from there? What’s the base price/volume combination we need to be profitable, and how realistic is it to significantly increase our profit margin over time? What could prevent us from doing that?

Structurally, is it an industry where companies have advantages of size and economies of scale? Are there ways to grow the business organically or through M&A? What multiples will I likely have to pay for companies I acquire, and is that number a large enough discount from the multiple I’d expect my company to trade at? This is important because the arbitrage between our cost of capital and what multiple we’re able to buy companies at is the biggest value-creation lever in a roll-up. Improving the actual profitability of the business is the second-biggest lever.

Is there a technology threat or opportunity or both? For example, are there ways to automate business processes and drive customer service higher at a lower cost of labor? How could AI impact the industry, both positively and negatively?

Armed with a short list of promising industries that satisfy these fundamental criteria, I’m ready to look below the surface.

I use a three-part methodology for my research: I educate myself on the industry as thoroughly as possible, compile a list of questions that matter, and then do my best to get in front of the most knowledgeable experts I can find on each topic. It’s not a perfectly linear process, because more questions arise as I continue my research, but that’s the basic structure.

I start by reading everything I can get my hands on—journals, periodicals, newspapers, trade publications, employee reviews on web-based recruiting sites, you name it. I look at all the websites and social media of the major players and the up-and-comers in the industry. I set Google Alerts for industry CEO names or other keywords, and I watch lots of YouTube interviews with CEOs. I also use paid services like Bloomberg, AlphaSense, and Thomson Reuters.

The most time-consuming task in my methodology is processing all the digital information that I accumulate; it’s a far cry from 44 years ago, when I physically went to the library to start researching industries. But I’ve got a team of super smart people who are good at distilling tons of source information. As I go through the material, I note my observations in preparation for the next step—my interviews with experts. After absorbing a lot of data and arming myself with questions, I seek out people who live and breathe the industry I’m considering. Some of this can be done with video chats, but this phase is more about getting face-to-face and listening intently.

I love talking to CEOs who have a track record of successfully growing businesses and creating substantial shareholder value. We share a similar language combined with experiences that are unique to our respective industries, which tends to make the meetings mutually beneficial. I also belong to the Business Council and the Economic Club of New York, which are valuable networking resources for me. They give me an entrée to CEOs in almost any industry I’m interested in learning more about.

In addition to CEOs, I seek out investment bankers who are most active in the industry and who know it deeply—bankers who have close relationships with management teams, have advised on lots of acquisitions in the space, and have raised billions of dollars of capital for these clients.

I also talk to venture capital firms, because they spend a lot of time looking at the big trends in different industries. And, I tap buy-side institutions, like Fidelity, Invesco, Orbis, and Cercano, and successful fund managers who have battle scars from investing in the industry. They know the leading players—companies and customers—as well as the risks and growth factors. They’ve already made and lost money in the industry, so I want to know what lessons they learned from those experiences. Industry vendors are also a good source; they have a sense of the trends that could drive changes in the market environment.

Shareholder activists often have important insights as well. And I reach out to journalists who know the industry because, by nature, they’re a skeptical bunch, and I want to hear their perspectives.

Trend-spotting an industry requires objectivity and open-minded analysis. I don’t pick an industry just because it’s in vogue. My team and I make detailed lists of pros and cons and create word clouds to illuminate macro themes from the information we’ve gathered. This helps to uncover an industry’s strengths and defects from the standpoint of making money for investors, which is the prime mission of a public company.

After completing these steps, I know a great deal about the industry I’m considering, and I can detach myself from distracting details to lock on to the big questions. What direction do I think the industry will move in over the next five years? Ten years? Inevitably, those answers will be affected by tech, and especially by artificial intelligence.”

My take:

Brad Jacob’s not just looking for short-term gains; he’s aiming to understand the big picture and align himself with the forces that drive real value over time. Whether it’s technology, demographic changes, or shifts in market behavior, getting the major trend right is what separates a sustainable business from one that’s just scraping by.

Jacobs’ laser focus on these trends goes beyond just being a successful business leader—he’s essentially acting like an investor. The key difference is that he’s hands-on in his investments. He doesn’t just throw money at opportunities; he deeply engages with the industries, the key players, and the major shifts within them. This is something that should resonate with any serious investor. If you can identify and position yourself within these trends, even if you make a few smaller mistakes along the way, the larger forces will carry you forward.

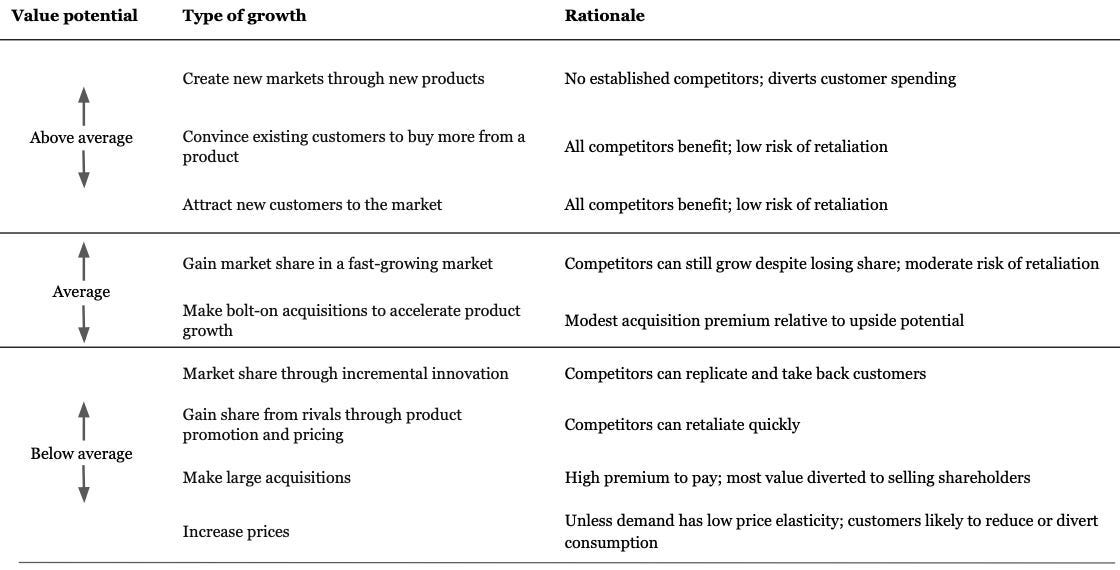

Often, as investors, we get stuck worrying about quarterly earnings or short-term stock price fluctuations. But, as Jacobs points out, it’s understanding the major trends that really matters. His approach shows that if you can identify a growing industry and figure out how to scale within it, the rest tends to fall into place. The McKinsey book Valuation explains this in great detail—why organic growth in industries with strong upward trends generates far more value than those in stagnating sectors.

So, is Jacobs any different from the rest of us? Not really, except that he’s more active in his investments. His deep understanding of the industries he enters allows him to make informed decisions that compound over time. For him, getting the big trend right has been a key lever of success, and that’s something all of us can apply in our own investment strategies.

4. M&A—Go big or go home!

“A fellow CEO laid this out for me graphically once when we were talking about M&A deals. Think of M&A as having four quadrants defined by size and risk, he said. Big, low-risk deals are the ones everyone wants, but they don’t exist. Small, low-risk deals do exist, but you can’t make much money from them because of their size. Small, hairy deals are the worst quadrant, because the reward is limited and the odds are stacked against you, so why bother? The bingo quadrant is the big, hairy deals. If you can find a big, hairy deal with solvable problems, that’s where the real money is.

If you plan to do M&A, you have to rearrange your brain to lean into those big, hairy deals and figure out how to cut off the hair and de-risk. You’ll need to be flexible, fearless, and open-minded, and stay attuned to your internal chatter. This is where your rearranged brain is going to kick in and look for solvable problems in big, hairy deals. Figure out whether these are problems you can address, either by removing them or by quantifying them and living with them. If not, move on.

The easiest way I know to create tremendous shareholder value is to buy businesses at profit multiples lower than the multiple our stock trades at, and then significantly improve those businesses.

The mechanics of M&A are fairly simple; anyone can buy a company by signing an agreement and wiring the money. So, why isn’t everyone doing it?

For one thing, there’s a certain amount of risk involved with each acquisition, and that needs to be offset by higher-than-average rewards. It’s a good feeling when we announce a deal and the stock price goes up that day, but that’s not the point. A good M&A deal should drive stockholder appreciation over the next five or ten years. Here’s how my team runs the numbers to look at a potential return, calculated on the most recent available earnings of the acquisition target.

We use ten years of earnings at zero growth as a baseline. From there, we make assumptions about what kind of organic revenue growth rate we can achieve in the business over ten years, and what kind of margin we can realize. We also estimate how much annual and cumulative cash flow the operation will generate or consume over ten years. For us, these projections need to be substantially higher than what the target is generating now, either because of the synergies inherent in being part of our larger company, or because we’re more accomplished operators, or both. There’s no such thing as a sweet deal without a clear path to significant growth.

We also stress-test every element of our projections, including the underlying assumptions. How likely are we to hit the base-case projected numbers? What is the upside scenario? The downside scenario?

I’ll only do deals where the downside scenario is still good for the company, the base case is excellent, and the upside case is off the charts. And I’m not willing to accept any significant chance that an acquisition won’t hit at least its base-case projections. If our analysis shows more risk than that, I’ll move on.

So, why do most companies fail at M&A deals, sometimes spectacularly? And why do most board members who see acquisitions as an easy road to value creation end up regretting signing off on these transactions? Experience is a big factor. Until you gain enough experience to mitigate M&A risk yourself, you’ll want to weigh the pros and cons of using a management consultant.

As a general rule, I only hire consultants for M&A when the value I expect them to add is at least ten times their fee. I can control this to a large degree by utilizing their resources in high-impact areas, like salesforce effectiveness, procurement, SG&A rationalization, and pricing. Consultants can also add value by analyzing large amounts of data or lending people to help with the workload. Their support lets our acquisition team move more quickly when multiple opportunities are under review.

I’ve been asked how we avoid getting bogged down in data murk when analyzing a target, particularly when it’s a large, complex acquisition. It helps to be clear up front about what the rationale is for buying the business, and then focus on whether that holds up during analysis. In its most fundamental form, the rationale for any acquisition should be, How will doing this deal contribute to the two main drivers of shareholder value, which are pleasing customers and propelling financial results? Put another way, How will doing this deal convince more customers to wire money from their bank account to ours?

I like to ask my key salespeople how they think our existing customers will react if they hear we bought Company X. Will they be happy because it adds value to what we offer? Or will they see little or no benefit to them, and worry that we’ll be distracted?

For me, the decision is unequivocal: If an acquisition doesn’t create shareholder value by producing a high return on invested capital, if it doesn’t help us thrill our customers, or differentiate our offering, or fill a strategic gap, then it will just make us bigger, not better.

The most effective way to understand not just the company but also their operating environment is by working as hard as the most diligent junior analyst at an investment fund—do disciplined, meticulous, bottom-up analysis. I want to be confident I understand the target’s strengths and weaknesses. We’ve created a systematic evaluation process that lets us move quickly, with less risk. And while there’s no one-speed-fits-all in M&A, faster is almost always better. Here are some of the specific questions my team and I answer as thoroughly as possible before we contact a prospective seller:

What will be the big drivers of profitable growth in this business over the next five to ten years? What do we have to believe in order to be confident we’re going to achieve that growth? Are the assumptions underlying these beliefs reasonable or easily derailed? Are there big hockey sticks to the growth of revenue and margin without credible explanations for them? Can we accelerate scale more rapidly and at a much lower cost base by deploying AI, automation, or robotics?

What are the synergies we can expect from the integration? If the operational execution isn’t up to par, is this something we have the capability to rectify through training and/or our technology? What are the redundant positions, overhead, and real estate costs? What procurement savings can we realize from the added scale? Is there an opportunity for cross-selling to the rest of our company?

What’s the level of morale in the organization? Are the right people in place, with an effective organizational chart? Where might they be overstaffed or understaffed? Is the salesforce top-notch, or is there an opportunity to train them to be more effective? The same question holds for the human resources and financial planning and analysis staff. Are the compensation plans properly structured to motivate people to contribute to the business plan, or is that another opportunity to improve?

And externally, how do customers regard this business? Is pricing too high or too low to be optimal for the market? Are there any trends in government regulations or political policies that could help or hurt the business?

Questions like these apply to almost every potential acquisition and help to keep the process on track. My team is both thorough and fast during the evaluation phase—telegraphing the seriousness of our intent.

The flip side of moving quickly is the pressure it can place on an acquisition team to get an agreement signed. One way to keep up the pace but avoid the pressure is to talk to multiple acquisition targets simultaneously so that you never feel you must do any specific deal.

I’ve also never knowingly done a deal that was dilutive to my company’s earnings. There were four or five times where an acquisition didn’t go according to plan and ended up being dilutive. But I’d estimate that 99 percent of the time our deals were accretive and had nice synergies to them.

Lastly, before I finalize an acquisition, my team puts together an integration playbook that’s a combination of math and music—hundreds of prescribed action points, but with room to be creative in response to the human part of the integration. Well in advance of closing, we’ve visualized every aspect of the process that will harmonize the acquired operation within our company. Every integration is an abstraction until you make it a reality, and there’s a great deal of satisfaction to be found in seeing that outcome come to fruition.

A fundamental mistake I made early in my M&A career was not attaching enough priority to understanding the culture of a prospective acquisition. It’s hard, if not impossible, to make wholesale changes to a business culture. The goal is to buy companies with cultures compatible with yours so that change can happen naturally, and for the benefit of everyone, as the integration proceeds.

One of the best uses of my time in the due diligence process is to do face-to-face talks with the top 15 or so people in the company we’re in the process of buying. I give these interviews an extra-high priority. They take about 90 minutes each, and I get the gist of what’s going on inside the company, the positive and the negative. I also get a sense of whether these are straightforward people I can trust. As a bonus, some of the information shared during these talks can help my team anticipate the improvement initiatives that will be needed for the integration playbook and start executing on them right away.

The sooner we can bring an acquired business into our technology ecosystem, the better. We want one enterprise platform, one human resources system, one CRM (customer relationship management) database for salesforce management, one business intelligence database, one internal social media community, one KPI (key performance indicator) dashboard, one training curriculum, and one email system. In addition, every new employee gets our procedures and policies manual, including our code of business ethics.

We place a priority on closing the acquisition books cleanly and standardizing the financial statements, monthly operating reviews, and budget so everyone is using the same format to present the numbers. We also move everyone to our incentive compensation plans and benefits programs. That way, we can benchmark people and locations, and instill accountability.

Operational integration also applies to the brand. I like to update the branding of an acquisition as soon as possible after signing the deal so that we’re presenting a uniform image internally and to the world. For example, there’s nothing that looks more amateur than salespeople going to meetings with different business cards and without standardized job titles.

We also set internal and vendor deployment schedules for rebranding the acquired operations with our company’s name and logo, including the installation of new signage. Ideally, a visitor to any one of our sites won’t be able to tell whether we opened that location from the ground up or we acquired it ten years ago, or one year ago.

Those are the big, chunky objectives at the top of our integration list. From there, we move on to the rest of the operations, including shared services like IT, finance, accounting, sales, marketing, procurement, and HR. And we strive to do it all seamlessly, because we also acquired customers in the deal, and they’re watching us daily to see how we perform.

We’ve never gone wrong by leading into an integration with the big, mission-critical parts of the operations. We don’t want to be operating two different businesses—we want clean numbers, fast data, and channels that allow us to share information consistently, to lever the high-caliber management team I’ve put in place.

A lot of mystique surrounds M&A integrations, but experience has taught me that it’s all quantifiable. When we acquire a company, the to-do list can stretch to hundreds or even thousands of tasks needed to make the integration work. My strong preference is to assign these tasks to individuals, not working groups. If we have one person owning each task and being accountable for achieving it on time, we’re more likely to succeed than if the task is owned by a group.

I also establish a regular cadence for monitoring progress throughout the integration, typically daily or weekly, or less frequently for tasks that take time to implement. With the cadence set, there’s less confusion about progress against the plan, or who has the wheel on a given task.”

My take:

When it comes to M&A, I’ve always been skeptical. Well, the truth is I was eager towards acquisitive companies in the past, but became wary. There’s a lot about the typical M&A playbook that doesn’t sit well with me, especially the idea of multiple arbitrage—buying companies at lower multiples to get a quick bump in value. It sounds appealing on paper, but the reality is far more complex. In most cases, the seller knows a lot more than the buyer, and the chances of scoring a great deal are slim. No one is out there handing over incredible businesses at 3-4x EBIT unless there’s a catch. Yet, there’s no shortage of CEOs who claim they can grow by buying up companies at bargain prices, and many investors eat that up without questioning the underlying risk.

Jacobs, however, takes a different approach. I’ll admit, I was initially skeptical of his aggressive M&A strategy—buying businesses at lower multiples, restructuring, and integrating them tightly into his own operation. On the surface, it sounded like just another risky roll-up strategy, but Jacobs has proven time and again that he knows how to extract real value from these deals. He doesn’t just buy companies for the sake of growth; he buys them because he believes he can significantly improve them.

There’s something to be said about his ability to make the hard changes that others either can’t or won’t. He’s not just collecting businesses—he’s optimizing them. This is where he differentiates himself from the copycats who talk about buying up companies at low multiples, expecting the value to magically appear. Jacobs knows that value creation in M&A is far from automatic. He’s methodical, integrating businesses tightly, restructuring when needed, and holding each piece accountable to the larger strategy. It’s a hands-on approach, and while it’s not the only way to succeed, it works for him.

It’s important to remember that there’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to acquisitions. Some companies, like CSU, have thrived by buying businesses and leaving them to operate independently with the right incentives in place. Jacobs goes the opposite route, implementing strict integration processes, down to the branding and management systems. And here’s the key lesson: every company, every industry, has its own dynamics. What works for one won’t necessarily work for another.

As investors, it’s easy to let personal biases blind us. We may not like the idea of aggressive M&A or think multiple arbitrage is too simplistic, but Jacobs proves that success in M&A is all about execution. His strategy works because he knows when and where to make the right changes, and he’s willing to roll up his sleeves and do the hard work. This is a reminder to keep an open mind and recognize that different approaches can work, depending on the company and the industry. Jacobs shows us that in the end, every master has their own playbook—and sometimes it’s worth studying, even if it’s not your first choice.

Some other quotes:

“A lot of employees who join us through M&A have never been asked, “What do you think the business could be doing better?” Ask them!”

“It’s important to keep the key talent in an acquisition. Also, be bold about identifying people who aren’t moving the company forward and offer them a generous exit package.”

“To create billions of dollars of value, you need a team of people who are smart, hardworking, honest, and kindhearted.”

“It’s better to be slightly understaffed, but not badly understaffed. A team that’s appropriately lean has a more concentrated focus and gets more done.”

“I want go-getters with big egos on my team—self-confident winners who are out to conquer the market and make a bundle. At the same time, they need to genuinely respect others. Even a hint of arrogance can be a red flag. To guard against it, I ask myself two questions when assessing a candidate in my one-on-one interviews. First, “Can this person think dialectically?” That is, are they capable of thinking from multiple perspectives, and reconciling streams of information that seem to flow in different directions? And second, “Are they capable of changing their opinion?” Rigid thinkers, at any level of intelligence, are less valuable to the team because they’re mired in their own points of view.”

“Hire ambitious people who want to accomplish big things and make a lot of money.”

“Don’t be cheap with what you pay for talent. Tie compensation to performance.

My advice to prospective CEOs is to participate in the intentional design of incentive plans, and not delegate them as strictly an HR or talent management task. It’s also important to customize the plans for different roles within the organization, keeping the domino effect in mind.”

“All five companies I founded were successful in establishing incentive plans that gave our employees a clear sense of the benchmarks and a fair chance of meeting them through a concerted effort. If you get either of these components wrong, your people aren’t going to be motivated by the monetary opportunity, effectively defeating the whole purpose of incentives. I’m usually not in favor of putting a cap on incentive compensation. I want my people to feel encouraged to run as far and fast as they can. Caps can have the opposite effect.”

Some additional resources below:

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Anker Capital is a regulated investment firm (www.anker-capital.com)

We currently offer segregated accounts for qualified professional investors. If you are interested, feel free to contact us at investors@anker.ag

Disclosure: This post and any attachments are for general informational purposes only regarding our activities and do not constitute investment advice, or an investment recommendation for any investment product.

The author or Anker Capital Management may own the securities discussed. Please read our Legal & Regulatory Disclosures for further details.

Nice post!

Thanks for great summary!