#81 The Passive Index Bubble: Myth or Reality?

Reflexivity, Inelastic Markets, and the Role of Marginal Investors

We all love index funds, right? They’re cheap, easy to understand, and—let's admit it—often beat the pros. "Buy the market, relax, and watch your wealth grow," they said. And it worked brilliantly… until everyone else also decided it was brilliant.

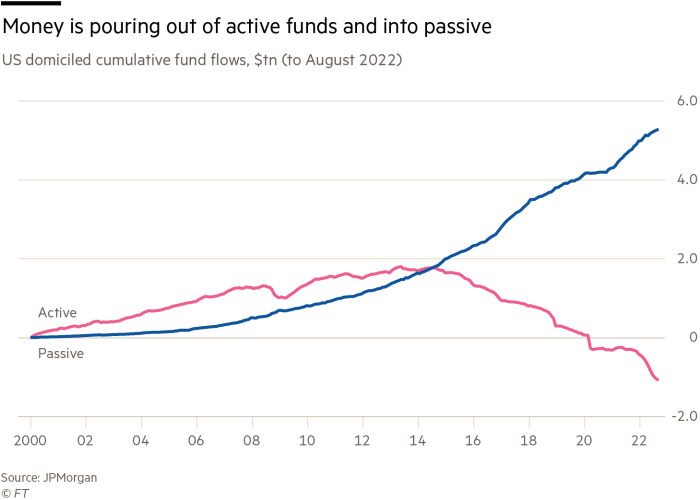

Now, there’s just one little issue. What happens when everybody decides to follow the same strategy? Michael Burry, and many other money managers, recently called passive investing "the bubble of our time." But could he be exaggerating, or is the oracle of "The Big Short" onto something big again?

The argument goes like this: with massive amounts of money automatically flowing into the largest companies (think Apple, Google, Microsoft, etc.), passive investing might quietly be distorting how prices are set. It doesn't matter if these stocks are ridiculously expensive—passive funds just keep buying. After all, who cares about boring things like valuation when the goal is just to mimic an index?

But wait, there's a twist. According to the Austrian school (think Böhm-Bawerk, Hayek, and many more), prices aren't set by clueless algorithms, but by marginal investors—real, breathing humans who actively choose to sell or hold. So, theoretically, someone rational should step in and keep prices grounded, right?

Here’s where things get interesting. What if these rational marginal investors… aren't that rational after all? Or even worse: what if the passive flows themselves create a self-fulfilling prophecy, feeding into George Soros’s beloved concept of reflexivity—where rising prices attract more money, pushing prices even higher, until reality finally wakes everyone up in a pretty harsh way?

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

I. How Passive Investing Could Create a Bubble

Let’s face it: passive investing has become the avocado toast of finance—trendy, affordable, and almost universally loved. Over the past decade, everyone from your dentist to your Uber driver has embraced the idea of buying index funds or ETFs. And who can blame them? Paying lower fees and avoiding expensive fund managers who often underperform sounds like common sense.

The problem is, when billions upon billions flow mechanically into these index funds, the money doesn't politely ask: “Hey, is this stock fairly priced?” Nope, it just buys. If Apple represents 7% of the index, 7% of every fresh dollar coming in automatically buys Apple shares, regardless of whether it’s trading at 15 or 50 times earnings. Fundamentals? Valuations? Please, don't bother the algorithm with such trivial matters.

The outcome is a strange market dynamic. Passive investing heavily favors large-cap stocks, particularly mega-tech companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, and friends—essentially, the usual suspects. So, guess what happens? These giants just keep getting bigger, attracting even more inflows, creating a self-feeding cycle..

David Einhorn, the once-famous value investor who now seems as frustrated as your grandpa trying to set up Netflix, recently complained that even stocks with excellent fundamentals don't go up if they're outside popular indexes. Why? Simply because there are no passive investors around to mechanically buy them. He described it beautifully (and bitterly): he's forced to buy ridiculously cheap stocks—think companies trading at four or five times earnings, practically giving away free cash—because he “can't count on other investors” to notice them anymore.

But perhaps the strongest argument that passive flows distort the market is the so-called Inelastic Market Hypothesis, which sounds fancy enough to impress your friends at dinner parties. According to economists Xavier Gabaix and Ralph Koijen, the market is far less responsive than previously believed. A tiny bit of money entering the market can have a massive impact on prices. Their math shows that for every dollar entering passive funds, market value can increase by about five dollars. Yes, five! It’s like throwing a pebble into a pond and getting a tsunami back.

In simple terms, markets are becoming more fragile because fewer active investors step in to keep prices sensible. Instead, they're quietly watching the passive parade inflate valuations, hoping not to miss out. Sounds familiar, right? It’s exactly the kind of herd mentality we thought indexing was supposed to avoid.

And here’s the kicker: the more passive investing grows, the stronger this weird feedback loop becomes. As valuations inflate, index funds look even smarter, attracting more money and pushing prices even higher. Until, of course, someone finally decides the music is too loud and pulls the plug.

II. Marginal Investors and the Austrian Perspective

So far, we've painted a picture where passive investing seems unstoppable, blindly pouring billions into large stocks without a second thought. But hold on a second—markets aren't actually run by robots (at least not yet). Behind every trade, there’s always someone on the other side deciding to sell, buy, or hold. And that's precisely where our Austrian friends—economists like Böhm-Bawerk and Jesús Huerta de Soto—step in with their concept of "marginal investors," or marginal pairs, as they call them in fancy economics terms.

Imagine you’re at a farmers market. You spot an avocado and decide you’d pay a maximum of 3 euros for it. The vendor, however, won’t let it go for less than 2 euros. As Austrian economists explain, your avocado trade will only happen somewhere between these two valuations—2 euros (the seller’s lowest price) and 3 euros (your highest). Now, if suddenly more avocado-loving hipsters arrive, desperately bidding up the price, the vendor smiles widely, raises the price, and sells it to whoever's willing to pay the most. That highest-paying hipster is your marginal buyer—the one who actually determines the final price.

In financial markets, the marginal investor works the same way. Despite all those passive funds automatically buying Apple or Google, at the end of the day, the actual price of Apple stock is set by the last active investor willing to sell at the going market rate. Even if millions of passive investors mechanically buy, they still need active sellers who consciously agree to sell at the current price and active holders who value the business more than the current market price.

In theory, this setup sounds fantastic because it means prices should always remain anchored to reality. Active investors would sell overpriced stocks and keep everything rational, right? Well, theory and practice often have a complicated relationship.

In reality, marginal investors might not be the cool-headed rational players that Austrian economists idealize. Instead, they're humans—filled with emotions, FOMO, and, let's face it, sometimes questionable judgment. So, what happens if these supposedly "active" marginal investors start behaving irrationally, following the herd instead of fighting against it?

Think about it this way: If you're an active fund manager and everyone around you is piling into Apple stock because it keeps going up, how likely are you to risk your job by betting against the crowd? Not very. Instead, you’ll probably quietly join the herd, rationalizing it by mumbling something about momentum or "not fighting the Fed." Ironically, this makes the marginal investor—the one who sets the price—more of a trend-follower than a contrarian voice of reason.

Therefore, even if passive funds aren't directly deciding the prices, their continuous inflows push marginal investors into irrational decision-making. The result? Prices keep climbing beyond sensible valuations, and our heroic marginal investors become reluctant followers rather than brave guardians of rationality.

So yes, markets still technically have active participants at the helm—but perhaps the helm is being steered by emotion rather than logic. And that might be the real issue beneath the passive investing bubble debate.

III: Reflexivity, The Soros Perspective

George Soros is one of those people who made billions not just by being smart, but by deeply understanding human stupidity. His secret weapon? A concept called reflexivity—which sounds complicated but basically means that market beliefs can shape reality, creating self-reinforcing cycles. It's a fancy way of saying that sometimes the market behaves less like a rational calculator and more like a teenager following TikTok trends.

Here's how it works: Imagine investors start buying tech stocks because they believe tech stocks will go up. As prices rise, people see their neighbors getting richer and think, "Wait, I want some of that easy money too!" More money flows into those stocks, pushing prices even higher and confirming the original belief. Prices climb, expectations soar, rinse, repeat—until reality eventually kicks in.

Passive investing could be fueling a similar reflexive cycle. Index funds pour money into large-cap stocks automatically, driving prices higher. Rising prices create the illusion of success ("Hey look, my passive fund is crushing it!"), which then attracts even more investors, causing more inflows, and—you guessed it—even higher prices. It’s a beautiful (or terrifying, depending on your view) loop that reinforces itself without regard to fundamentals.

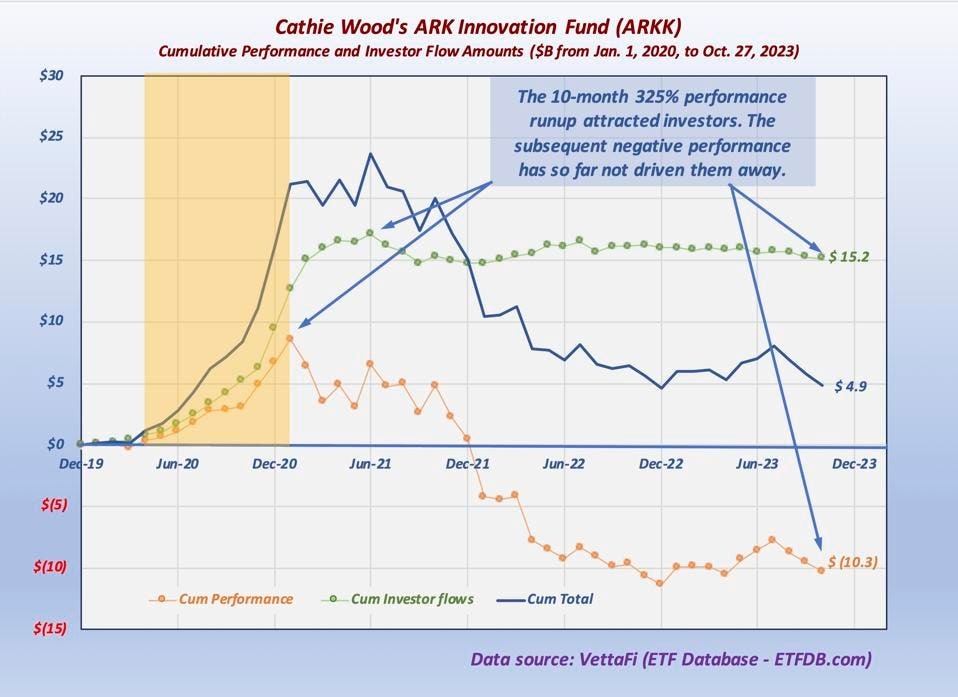

We've already seen this story play out vividly with Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovation ETF—the poster child for reflexivity. Back in 2020, ARK became a rockstar investment, attracting billions of dollars into disruptive tech companies. Prices soared, not because the underlying companies suddenly discovered magic beans, but because more money was chasing the same limited stocks. People invested because ARK’s price was going up, and ARK’s price kept going up because people invested. Beautifully irrational, isn't it?

Then came reality knocking at the door. Once the market turned, those inflows became outflows, forcing ARK to sell holdings at falling prices, creating a vicious cycle downward. The very mechanism that drove ARK’s prices skyward—reflexivity—now brutally reversed itself. Investors realized (perhaps painfully late) that gravity still existed.

Could the broader passive-investing boom face a similar fate? Possibly. As more investors pile into indexes and ETFs, the market could become increasingly fragile. Any significant reversal—caused by a recession, inflation fears, or simply a shift in sentiment—could trigger a powerful reflexive correction, sending valuations spiraling downward as quickly as they once rose.

In short, passive investing has quietly built its own self-feeding machine, one that’s powered by optimism today but could easily shift gears tomorrow. Reflexivity reminds us that markets aren't just driven by facts and logic—they're often driven by what people believe (or fear) might happen next. And sometimes, those beliefs can become reality—until reality decides it’s had enough.

IV: Why Active Investors Haven't Corrected These Distortions

At this point, you're probably wondering: “If passive investing is inflating this bubble, why aren’t all those smart, active investors making easy money shorting the overpriced giants and buying those neglected small-caps?” Good question—and the answer isn't that active investors suddenly lost their IQ points. Instead, they're trapped by a set of invisible constraints that quietly sabotage their attempts at rational investing.

First, consider the problem of liquidity. Imagine you're managing billions of euros. Now try investing in some obscure, undervalued small-cap stock. You quickly realize you can’t invest meaningful sums without driving prices to the moon yourself—or getting hopelessly stuck if you ever try to sell. Large investors need large playgrounds, which pushes them toward huge, liquid stocks like Apple or Microsoft—the very same companies already bloated by passive flows.

Then comes the infamous institutional career risk—probably the most underrated force shaping professional investors' decisions. Put yourself in a fund manager’s shoes: if you buy Apple because everyone else is buying Apple and the stock tanks, you can shrug and say, "Hey, it wasn’t my fault, everyone else was doing it!" But if you buy some weird, undervalued stock that nobody else owns and it crashes, your clients and bosses will look at you like you're the guy who wore jeans to a wedding. As economist John Maynard Keynes once said, it's always safer for professional managers to "fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally."

This leads us neatly into another subtle villain: benchmark hugging. Most active managers are judged by how well they perform compared to an index—yes, the same indexes that are now full of overvalued giants. Straying too far from these benchmarks can quickly get uncomfortable. Underperforming your peers because you dared to invest differently? You’re asking to get fired. So instead, many active managers quietly mimic index positions—becoming "closet indexers”.

As a result, undervalued small-cap stocks remain neglected. Yes, they might be cheap. Yes, they might even promise juicy returns. But without large institutional money backing them, they lack the oxygen needed to ignite price discovery.

So, despite the apparent easy-money opportunities created by passive distortions, active investors have been strangely slow—or simply unable—to capitalize on them. They aren’t blind or foolish. They’re just rationally responding to the constraints of their world: career pressures, liquidity limitations, and the cold reality of following the herd.

Ironically, in a world increasingly dominated by passive investors who don't care about prices at all, the active investors who should be correcting market distortions find themselves caring about prices a bit too much—at least when it comes to their own job security.

V: Bubble or New Normal?

So, after looking at both sides, what exactly are we dealing with here? Is passive investing a ticking bomb ready to explode, or is it simply the new way the market works? Like most good debates, the answer is annoyingly nuanced.

On one side, you have the bubble camp, waving their red flags furiously. But the other camp—let’s call them the "new-normal crowd"—believes passive investing isn’t going anywhere. For them, indexing is like Wi-Fi or Spotify Premium: once you have it, you never willingly give it up. Why pay more to active managers who struggle to beat the market anyway? Passive investing might simply reflect a permanent structural shift—one where low-cost, broad-market funds become the default choice, forcing active investors into niche markets or private investments to find value.

This leads us to an intriguing possibility: a market bifurcation. Imagine two distinct financial universes. On one side, we have highly liquid mega-caps, driven by relentless passive flows. This segment acts more like a utility company—steady, boring, occasionally overpriced, and periodically prone to momentum-driven excesses. On the other side, we have smaller companies and overlooked niches, where active investors roam more freely, prices still move on real fundamentals, and bargains still exist—if you dare to search for them.

Maybe what we're seeing isn’t a traditional bubble, after all. Maybe it’s a “new normal” bubble, a hybrid scenario where distortions appear frequently but correct slowly, punctuated by bursts of volatility whenever passive inflows stall or reverse.

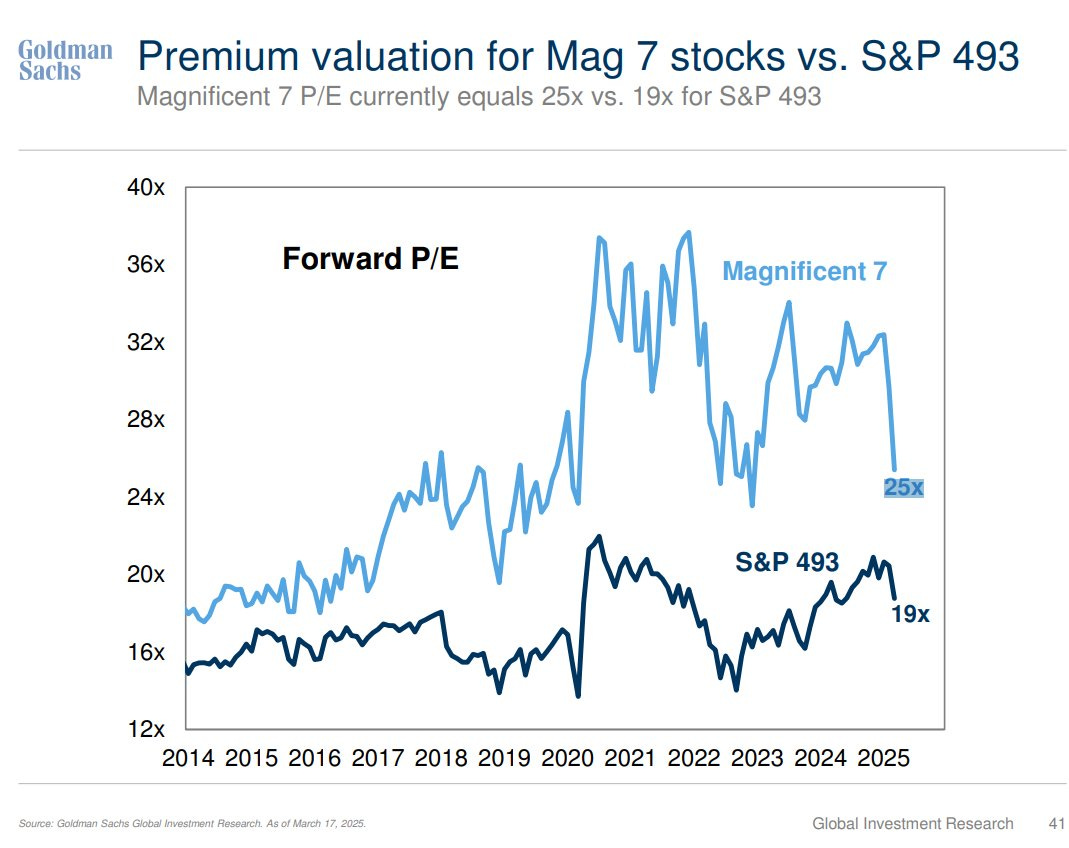

In recent weeks, we've seen something interesting unfold in the markets: the "Magnificent Seven" have suddenly started underperforming the broader indexes. This shift has led some to quickly argue, "Hey, doesn't this mean the passive bubble theory is dead?" But ironically, this recent drop may reinforce, rather than invalidate, the core arguments we've been discussing.

Why? Because when passive flows heavily favor certain mega-cap stocks, valuations can become increasingly fragile. Passive investing works wonderfully when money is steadily flowing into the market, but as soon as sentiment shifts—even slightly—the same mechanical process can accelerate a downturn. Those same stocks that benefited disproportionately from passive inflows also tend to get disproportionately hurt when money begins flowing out. In other words, the reflexive, inelastic mechanics we discussed can magnify moves downward as much as upward.

What we're witnessing now might actually be an early sign of what happens when the passive-investing machine starts reversing gear. When passive funds experience outflows or even just slower inflows, they mechanically sell stocks proportionally to their index weightings—meaning the largest, most liquid names suffer the most. So, paradoxically, this recent underperformance of the "Mag 7" could serve as further proof that passive-driven distortions not only exist but could also create increased volatility in both directions—up and down.

TL,DR

Calling passive investing a simple bubble might oversimplify what’s really happening. Yes, passive investing inflates valuations and can drive irrational market behavior, but labeling it purely as a bubble misses the bigger picture. Passive investing’s influence isn’t temporary—it’s reshaping the market itself.

Investors now must accept this reality: markets dominated by passive flows may offer fewer obvious opportunities, distort prices more frequently, and swing more violently during corrections. Yet, within this strange new landscape, there’s still hope. For those willing to step outside mainstream indexes, plenty of opportunities remain, especially among smaller, overlooked companies starved for attention.

The key is to recognize the environment we’re operating in: one where price discovery is slower, distortions linger longer, and reflexivity constantly threatens to tip markets into volatility. It’s a world where fundamentals eventually matter—but “eventually” might mean years, not months.

Ultimately, calling passive investing a bubble oversimplifies a complex issue. Yes, risks have risen, and yes, the market is changing profoundly. But rather than fearing imminent doom, investors might do better simply by adapting—acknowledging passive investing's strengths and vulnerabilities and navigating accordingly. After all, markets evolve, and the investors who succeed will be those who learn to ride the waves rather than complain about their size.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

Phenomenal piece! Well written and unique thoughts I haven’t heard before. Keep up the work, Javier!

Interesting article. Would be great to have more absolute numbers in to validate important facts. Some articles state that active investing is still >95% vs. passive investing. Example in German: https://gerd-kommer.de/marktanteil-passives-investieren/