If the soul of Europe is being eroded by over-regulation and bureaucratic inertia, what are the implications for its future? How did a continent once synonymous with freedom and prosperity come to be stifled by its own policies?

Through Zweig's eyes, we see a once-prosperous society on the brink of two world wars, contrasted with today's welfare states—lacking the youthful vigor to embrace an innovative future and potentially facing numerous risks.

Welcome to Anker Capital! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

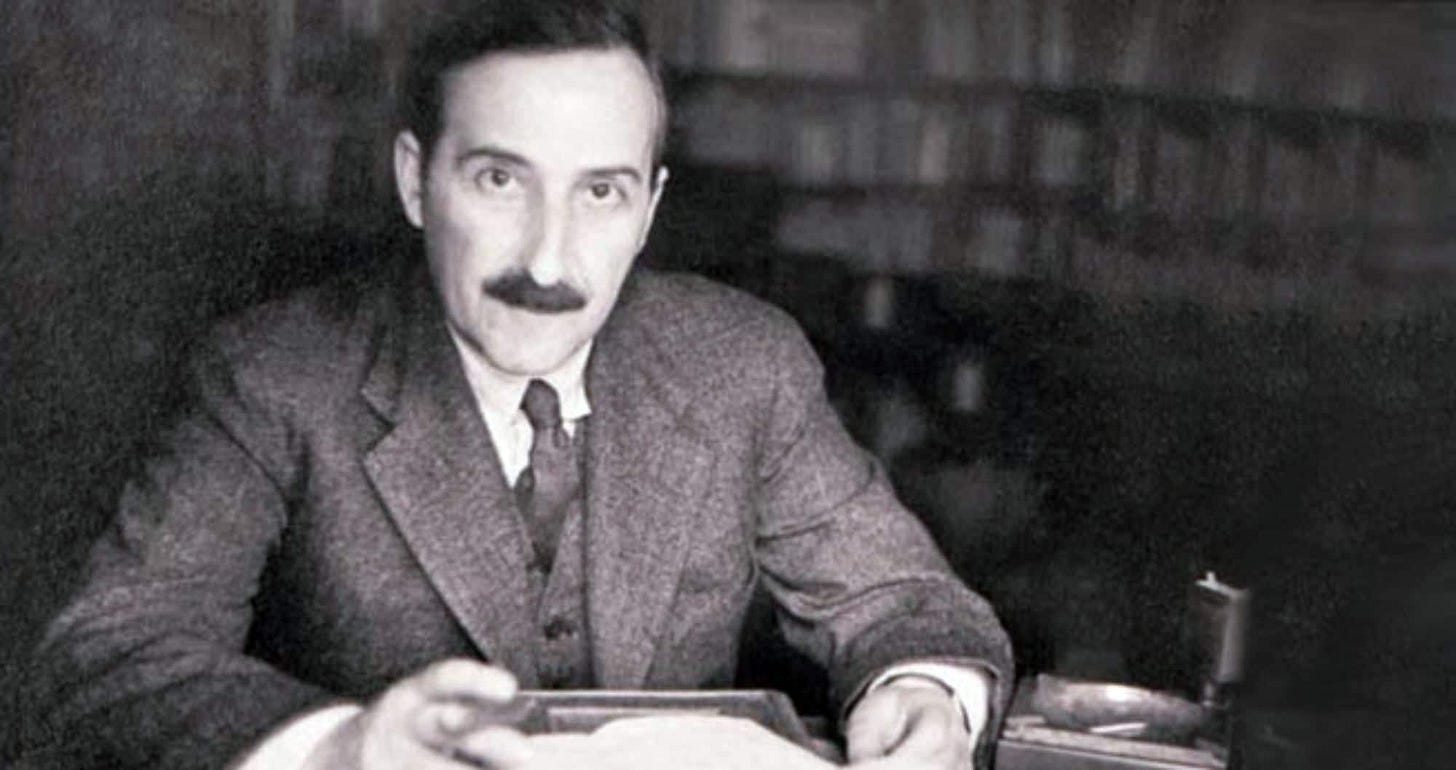

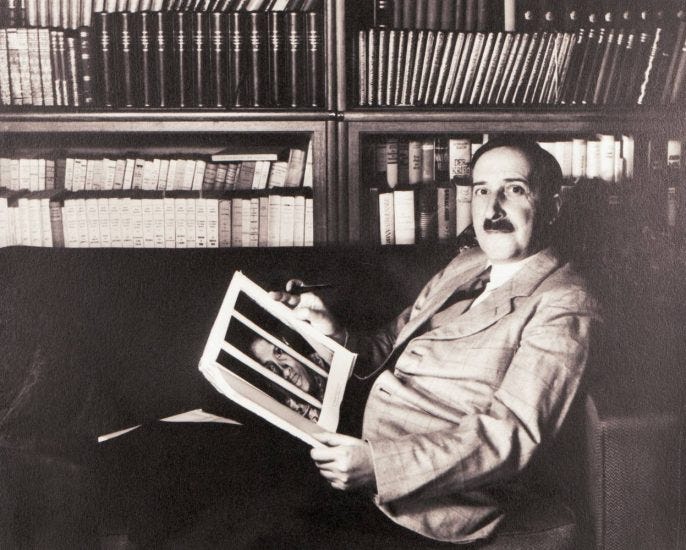

"The World of Yesterday" is not just a memoir; it's a poignant reflection on a lost world. Through Stefan Zweig's eyes, we see a Europe brimming with cultural richness and intellectual fervor, only to be torn apart by the brutal forces of nationalism and war. This book is a genuine gem of the 20th century, offering a window into a time of both great beauty and profound tragedy.

Among the many splendid passages, Zweig vividly describes his school years in Vienna at the end of the 19th century. Teachers were dull and uninspiring (unlike today), and he and his friends were consumed by thoughts of literature, poetry, and the theater. There are symbolic scenes, like when he was returning from Switzerland after World War I and witnessed the exile of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, Otto von Habsburg, on the platform of Feldkirch station, marking the collapse of an old world. Zweig also recounts his collaborations with Richard Strauss, writing librettos for his operettas, and Strauss's precarious relationship with the Third Reich.

Each chapter of the book is a seamless chain of remarkable experiences, showcasing the extraordinary life of Stefan Zweig. Through his masterful storytelling, we are transported to a time when Europe was both incredibly vibrant and on the brink of profound change.

1. The Values of a Prosperous Europe Versus Today

“Everything in our nearly millennial Austrian monarchy seemed to be based on the foundation of longevity, and the State itself appeared to be the supreme guarantee of this stability. The rights it granted to its citizens were guaranteed by the Parliament, a freely elected representation of the people, and all duties were precisely defined. Our currency, the Austrian crown, circulated in gleaming gold coins, thus guaranteeing its invariability. Everyone knew how much they had or were owed, what was permitted and what was prohibited. Everything had its norm, its measure, and its determined weight. Those who possessed wealth could calculate exactly the interest it would yield annually; officials or military personnel could confidently find on the calendar the year in which they would be promoted or retire. Each family had a fixed budget, knew how much to spend on housing and food, on summer vacations and ostentation, and also carefully reserved a small amount for unforeseen events, illnesses, and doctors. Those who owned a house considered it a secure home for their children and grandchildren; lands and businesses were inherited from generation to generation; when a baby still lay in the cradle, a coin was already deposited in the piggy bank or savings account for their future journey in life, a small "reserve" for the future. In that vast empire, everything occupied its place, firm and unchanging, and at the top was the elderly emperor; and if he died, it was known (or believed) that another would come and nothing would change in the well-calculated order. No one believed in wars, revolutions, or upheavals. Everything radical and violent seemed impossible in that era of reason.

This feeling of security was the most desirable possession of millions of people, the common ideal of life. Only with this security was it worth living, and increasingly broader circles coveted their share of this precious good. Initially, only landowners enjoyed such privilege, but gradually the masses also strove to obtain it; the century of security became the golden age of insurance companies. People insured their homes against fire and theft, their fields against hail and storms, their bodies against accidents and illnesses; they subscribed to life annuities for old age and deposited in their daughters' cradles a policy for their future dowry. Eventually, even workers organized, achieved stable wages and social security; domestic workers saved for old-age insurance and paid for their funeral in advance, in installments. Only those who could look to the future without worries enjoyed the present with a good spirit.

In this touching confidence in being able to shield life against any breach, despite the solidity and modesty of such a life concept, there was a great and dangerous arrogance. The 19th century, with its liberal idealism, was convinced it was on the right and infallible path to "the best of all worlds." Previous eras, with their wars, famines, and revolts, were looked down upon as times when humanity was still underage and not sufficiently enlightened.”

…

“This prudent way of expanding business, despite the temptingly favorable situation, fully aligned with the spirit of the time. It corresponded, moreover, in a special way, with the reserved and non-greedy character of the father, who had assimilated the creed of the time: safety first; for him, having a "solid" company (another favorite word of those times) with its own capital was more important than turning it into a large company based on credits or mortgages. The fact that no one had ever seen his name on a promissory note or bill of exchange and only appeared on the creditor side of his bank (of course, the most solid credit institution, the Rothschild bank) was the only pride of his life. He opposed any gain that involved the slightest hint of risk and never participated in other people's businesses throughout his life. However, if he became rich little by little, and increasingly richer, it was not thanks to bold speculations or long-term operations, but to his adaptation to the general method followed at that prudent time, which consisted of using only a discreet part of the income and consequently adding a more considerable sum to the capital every year. Like most of his generation, my father would have branded as wasteful anyone who carelessly spent half of their income without "thinking about tomorrow" (another of the habitual phrases of the security era that has survived to us). Thanks to this constant saving of profits, in that time of growing prosperity, when the State only thought of taking a small percentage even from the highest incomes and when industrial and State securities produced high interest, becoming increasingly richer in reality meant no more than passive effort for the wealthy. And it was worth it; savers were not yet robbed, as in times of inflation, the solvent were not cheated, and precisely the most patient, those who did not speculate, obtained better returns. Thanks to this adaptation to the general system of the time, my father, already at fifty, could consider himself a wealthy man, also according to international standards. But our family's lifestyle did not follow the rapidly increasing fortune until much later.”

“In no other European city was the passion for culture as intense as in Vienna. Precisely because the monarchy and Austria had had no political ambitions or many military successes for centuries, national pride had mainly focused on artistic predominance. From the former Habsburg Empire, which once dominated Europe, the most important and valuable provinces: German and Italian, Flemish and Walloon, had long since separated; the capital, the court's bulwark, the guardian of a millennial tradition, remained unscathed, immersed in its old splendor. The Romans had laid the first stones of a castrum, an outpost, to protect Latin civilization from barbarism, and after more than a thousand years, the Ottoman assault crashed against those walls. The Nibelungs had passed through here, and from here the constellation of the seven immortal stars of music illuminated the world: Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and Johann Strauss; all currents of European culture converged here; at court, among the nobility and the people, the German mixed blood ties with the Slavic, Hungarian, Spanish, Italian, French, and Flemish, and the true genius of this city of music consisted in harmoniously merging all these contrasts into a new and peculiar element: the Austrian, the Viennese. Welcoming and endowed with a special sense of receptivity, the city attracted the most diverse forces, relaxed them, softened them, and calmed them; living in such an atmosphere of spiritual reconciliation was a balm, and the citizen, unconsciously, was educated on a supranational, cosmopolitan level to become a world citizen.”

…

“I had lived ten years of the new century and seen India, parts of America, and Africa; I began to look at our Europe with renewed joy, more wisely. Never have I loved our Old World as much as in the last years before the First World War, never have I trusted so much in Europe's unity, never have I believed so much in its future as in that time when it seemed we were glimpsing a new dawn. But in reality, it was already the glow of the approaching world fire.

It may be difficult to describe to the generation of today, raised amid catastrophes, ruins, and crises, for whom war has been a constant possibility and an almost daily expectation, it may be difficult, I say, to describe the optimism and confidence in the world that animated us young people from the turn of the century. Forty years of peace had strengthened the economic organism of the countries, technology had accelerated the pace of life, and scientific discoveries had filled that generation's spirit with pride; a period of prosperity had begun to be felt almost equally in all the countries of our Europe. Cities became more beautiful and populous year by year; the Berlin of 1905 no longer resembled the one I had known in 1901: that imperial capital had become a metropolis and was splendidly surpassed by the Berlin of 1910. Vienna, Milan, Paris, London, Amsterdam: every time one returned there, one was astonished and felt happy; the streets were wider, more sumptuous; public buildings more imposing; shops more luxurious and elegant. Wealth was growing and spreading everywhere; even writers noticed it in the print runs that multiplied by three, five, and ten in a single period of ten years. Everywhere new theaters, libraries, and museums emerged; comforts like bathrooms and telephones, which had previously been privileges of a few, reached the petite bourgeoisie, and since the workday had been reduced, the proletarian had risen from below to participate, at least, in the small joys and comforts of life. Progress was in the air everywhere. Those who took risks won. Those who bought a house, a rare book, or a painting saw its price rise; the bolder and more prodigally a business was created, the more assured the benefits were. At the same time, a prodigious carefreeness had descended upon the world, because who could stop this advance, curb this impetus that kept drawing new strength from its own momentum? Europe had never been stronger, richer, or more beautiful; it never sincerely believed in an even better future; no one, except for four old wrinkled people, lamented like before, saying that "the old times were better."

…

Zweig offers us a nostalgic vision of a Europe where prosperity and stability were the norm, founded on the respect for private property, a sound and unaltered currency, and individual freedom. These elements were synonymous with prosperity and peace. There existed a pseudo-Victorian spirit of thrift and prudent capitalism, in contrast with modern consumerism. This stability and security allowed people to progress through effort and work, without relying on state handouts or selective, repressive, and partisan social justice.

Arts, culture, and progress flourish in free and wealthy societies. Similarly, the protection and concern for the environment arise in rich societies. Once basic needs are met, thanks to a level of wealth that is only achieved when a society is free and respects private property, individuals can devote themselves to non-vital tasks such as culture and, more recently, environmental protection.

However, today, over-regulation and a lack of innovation have undermined these pillars. The European Union, which began as a liberal hymn to free trade, has become a bureaucratic apparatus serving political elites. Recent calls for economic and population degrowth, though perhaps well-intentioned, are dangerous and ignorant. These proposals not only threaten to bring poverty, plunder, and hunger, but also undermine the principles that once made Europe prosper.

Instead of fostering a rich and free society, these ideas promote plunder and state dependency, increasingly distancing us from the ideal of peace and prosperity that Zweig described so eloquently.

2. Nationalism and Collectivism: Antithesis of Freedom

"It is precisely the stateless person who becomes a free man, free in a new sense; only one who is bound to nothing owes reverence to nothing. That is why I hope to fulfill the sine qua non condition of any truthful description of an era: sincerity and impartiality.

And I have stripped myself of all roots, including the land that nurtures them, as perhaps few have done throughout time. I was born in 1881, in a great and powerful empire, the monarchy of the Habsburgs, but don’t bother looking for it on the map: it has been erased without a trace. I was raised in Vienna, a twice-millennial and supranational metropolis, from which I had to flee like a criminal before it was degraded to the status of a German provincial town. In the language in which I had written and in the land where my books had won the friendship of millions of readers, my literary work was reduced to ashes. So now I am a being from nowhere, a foreigner everywhere; a guest, at best. I have also lost my true homeland, the one my heart had chosen, Europe, from the moment it committed suicide by tearing itself apart in two fratricidal wars. To my deep dismay, I have witnessed the most terrible defeat of reason and the most fervent triumph of brutality in the annals of time; never, ever (and I say this not with pride but with shame) has a generation suffered such a moral catastrophe, and from such a spiritual height, as ours has."

...

"Before the war, I had known the highest forms and degrees of individual freedom and afterwards, its lowest level in centuries. I have been honored and marginalized, free and deprived of freedom, rich and poor. Through my life, all the yellowish horses of the Apocalypse have galloped: revolution and hunger, inflation and terror, epidemics and emigration; I have seen the birth and expansion of the great mass ideologies before my own eyes: fascism in Italy, National Socialism in Germany, Bolshevism in Russia, and, above all, the worst of all plagues: nationalism, which poisons the flower of our European culture. I have been forced to be a helpless and powerless witness to the inconceivable fall of humanity into a barbarism unseen in times and which wielded its deliberate and programmatic anti-humanity dogma."

...

"One had to constantly submit to the demands of the State, surrender as a victim to the most foolish politics, adapt to the most fantastic changes; one was always chained to the collective, no matter how tenacious one's defense; one found oneself irresistibly trapped. Anyone who has lived through this era, or rather, anyone who has been cornered and persecuted during this period (we have not known many moments of respite), has lived more history than any of their ancestors. Today we find ourselves at a crucial point: an end and a new beginning. So, I do not act gratuitously when I conclude this retrospective look at my life on a certain date. It is because that day in September 1939 definitively marked the end of the era that formed and educated those of us who are now sixty years old. But if with our testimony we manage to pass on even a spark of its ashes to the next generation, our effort will not have been in vain."

Stefan Zweig, in his work, describes nationalism and collectivism as the most destructive forces against individual freedom. His testimony of having experienced the highest forms of freedom and, subsequently, its lowest level in centuries, resonates deeply with the current reality of Europe. According to Zweig, nationalism is the plague that poisons European culture, leading humanity into unprecedented barbarism.

In today's Europe, the rise of extremisms, from both sides, and collectivism (applicable to all political parties without exception) has restricted freedom and fostered a dependence on state handouts. This situation has created an atmosphere where individual progress and innovation are hindered by repressive policies and a lack of responsibility.

3. Education and the Shift in Values

"It is only from this singular point of view that one can understand why the State has exploited the school as an instrument suited to its purpose of maintaining authority. Firstly, they had to educate us in such a way that we learned to respect what was established as something perfect and unchangeable, the teacher's opinion infallible, the father's word indisputable, the State institutions absolute and eternally valid. The second cardinal principle of that pedagogy, which was also applied within the family, established that young people should not live too comfortably. Before they could benefit from a right, they had to have assumed the principle of duty, above all total obedience. We were taught from the first moment that, as we had done nothing in life yet and, therefore, had no experience, far from being in a position to ask for or demand things, we could only be grateful for what was granted to us."

This vision of education contrasts sharply with the current reality. In Zweig's time, the educational and familial systems instilled values of duty, effort, and responsibility. Young people were taught to respect established norms, to obey, and to be grateful for what they were given, understanding that rights were earned through the fulfillment of duties.

Today, we have seen a significant shift in these values. Modern education tends to focus more on rights than on duties. There is a growing emphasis on what one is entitled to demand rather than what one should contribute. This change has led to a society where rights are perceived as inherent, without recognition of the accompanying responsibilities. When a right is funded by another, it ceases to be a right and becomes a privilege.

4. The University and the Fallacy of Equal Opportunity

"And in those now vanished times, in Austria, the university still had a special, romantic aura. Being a student conferred certain privileges that placed young academics well above their peers of the same age. This uniqueness, perhaps outdated, was little known in non-Germanic countries, so its absurdity and anachronism require explanation. Most of our universities had been founded in the Middle Ages, in an era when dedication to science was considered extraordinary, and to attract young people to study, they were granted certain class privileges. Medieval scholars were not subject to ordinary justice, could not be detained or disturbed in their colleges by bailiffs, wore special attire, had the right to duel with impunity, and were recognized as a closed guild with their own customs and vices. Over time and the progressive democratization of public life, when all other medieval guilds and corporations dissolved, this privileged status of academics was lost throughout Europe; only in Germany and Austrian Germany, where class consciousness always imposed itself on democratic principles, did students continue to cling to privileges that had long been senseless and even turned them into their own student code. The German student, besides the civil and general one, especially arrogated a special kind of 'honor': precisely that of being a student. Whoever offended him had to give him 'satisfaction,' that is, face him with weapons in a duel, provided he was 'capable of giving satisfaction.' And according to this presumptuous assessment, a merchant or a banker, for example, was not capable of giving satisfaction, only someone with academic training, a graduate or an officer: no one else, among millions of people, could participate in the singular honor of crossing swords with one of those stupid, beardless youths."

...

"For me, Emerson's axiom, according to which good books replace the best university, has not lost its validity, and I remain convinced to this day that one can become an extraordinary philosopher, historian, philologist, jurist, and anything else without having to go to university, not even to high school. Countless times I have seen in practical life that secondhand booksellers often know books better than the very professors; that art dealers understand more than the scholars; that a good part of the initiatives and discoveries in all fields come from outside the university. As practical, useful, and beneficial as academic activity may be for average talents, I find it superfluous for creative minds, in whom it can even have a counterproductive effect."

The prevailing social dictate now is that all citizens must be equal before the law, and no other conception is socially accepted without risking being labeled as fascist. No other possibility is even considered. Yet, less than a century ago, students were not subject to the same laws as the rest of society. It might seem that now our politicians (wise guarantors of our liberties and protectors of our democracy) somehow have a different judicial status than the rest of us mortals. When society does not open itself to different forms of organization and believes that everything that exists now has always existed and that there is no better way, we fall into a latent and dangerous lack of improvement. Is it really so bad that different types of citizens are subject to different laws? Food for thought.

There is no better university than oneself: curiosity, the desire to learn, questioning things, and not accepting the status quo by default. The internet has done more for equal opportunity (all knowledge is there, within reach of anyone who wants to seize it) than any public policy in the last 100 years.

5. United States vs. Europe: A Contrast of Opportunities

"First impressions were formidable, despite New York not yet having the captivating nighttime beauty of today. The impetuous waterfalls of light in Times Square and the fantastic starry sky of the city that at night paints the real and authentic stars of the firmament red with millions of artificial stars did not yet exist. The appearance of the city, as well as the traffic, lacked the bold munificence of today, as new architecture was still being tentatively tried in some large isolated buildings; the surprising rise in the taste for shop windows and decorations was barely in its early stages. However, contemplating the harbor from the Brooklyn Bridge, always with a slight sway, and walking through the stone canyons of the avenues was a real source of discoveries and emotions, although, after two or three days, they gave way to a different, stronger feeling: the sensation of extreme loneliness. I had nothing to do in New York and, at that time, nowhere was a person without a job more out of place than there. There were no cinemas where one could be distracted for an hour, nor the small, cozy cafes, nor so many art galleries, libraries, and museums as today; in all cultural matters, the Americans lagged far behind our Europe. After visiting the main museums and monuments faithfully for two or three days, I wandered aimlessly through the icy, windy streets like a rudderless boat. Eventually, the feeling of absurdity in my wandering became so strong that I could only overcome it by making it more attractive with a stratagem: I invented a game with myself. I said I would be a completely alone vagabond, one of the many immigrants who didn't know what to do and who only had seven dollars in their pocket. I said: do voluntarily what they have to do out of necessity. Imagine that within three days, at most, you are forced to earn a living, look around and see how they manage here without contracts or friends to earn a salary quickly! With that, I started going from one employment office to another and studying the job ads posted on the doors. Here they were looking for a baker, there for an office assistant with knowledge of French and Italian, and further down for a bookstore clerk. At least this last job was a first opportunity for my imaginary self. So, I climbed three floors up an iron spiral staircase, inquired about the salary, and compared it with the rental prices of rooms in the Bronx that appeared in the newspapers. After two days of 'job hunting,' I had found, in theory, five positions that would have served to get by; in this way, I better understood how much space, how many possibilities this young country offered someone willing to work, and that impressed me. Moreover, all these comings and goings from one agency to another, my introductory visits to companies, allowed me to form an idea of the excellent freedom that reigned in the country. No one asked me about my nationality, religion, or origin, even though I had traveled without a passport (something unimaginable in our current world, a world of fingerprints, visas, and police reports). But there was work waiting for people; that, and only that, was decisive. The contract was signed in a few minutes, without the annoying intervention of the State, without formalities or unions, in those legendary times of freedom. Thanks to the efforts to 'find a job,' I learned more about America in those first days than in all the subsequent weeks, during which I toured, as a carefree tourist, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, and Chicago."

This contrast is even more evident today. While the United States continues to pioneer the development of new technologies like artificial intelligence, Europe seems trapped in a maze of over-regulation and bureaucracy. Technological revolutions are approached differently on both continents: in the United States, innovation is driven by competition and business freedom, while in bureaucratic Europe, the predominant response is to regulate what is not understood.

Instead of fostering an environment where citizens can become more productive and reduce their working hours thanks to efficiency and innovation, Europe often resorts to decrees to enforce changes in working hours. This approach not only limits the capacity for adaptation and growth but also stifles the entrepreneurial spirit that is crucial for economic and social progress.

Zweig foresaw, more than a century ago, the European decline compared to American prosperity. Today, his observations remain relevant, reminding us of the importance of freedom and minimal state intervention for the development of a dynamic and prosperous society. The lesson is clear: for Europe to regain its competitiveness and vitality, it must return to the principles of freedom and opportunity that once made it great.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Anker Capital is a regulated investment firm (www.anker-capital.com)

We currently offer segregated accounts for qualified professional investors. If you are interested, feel free to contact us at investors@anker.ag

Disclosure: This post and any attachments are for general informational purposes only regarding our activities and do not constitute investment advice, or an investment recommendation for any investment product.

The author or Anker Capital Management may own the securities discussed. Please read our Legal & Regulatory Disclosures for further details.

Impresionante artículo. Gracias por compartirlo

As always, such an interesting article. When investing for a long time, geopolitics have to be taken in consideration as they are a part of the safety of your portfolio. Not only safety as in losses, but also as in losing growth.

As an European investor, investing a part of your portfolio outside Europe is a must. Either directly or through international European businesses or Etf’s.

You made me buy the book this morning and I look forward to reading it and comparing it with today’s Europe.

But I am guessing it will be a fascinating read in itself. Thank you for the inspiration.